1. THE RIGHT DEVIATION IN THE COMMUNIST PARTY.

Comrades, I shall not touch on the personal factor although it played a rather conspicuous part in the speeches of some comrades of Bukharin's group. I shall not touch on it because it's a trivial matter and it's not worthwhile dwelling on trivial matters. Bukharin spoke of his private correspondence with me. He read some letters and it can be seen from them that although we were still on terms of personal friendship quite recently we differ politically now. The same note could be detected in the speeches of Uglanov and Tomsky. How does it happen, they say, that we are old Bolsheviks and suddenly we are at odds and unable to respect one another?

I think that all these moans and lamentations are not worth a brass farthing. Our organization is not a family circle nor is it an association of personal friends. It is the political party of the working class. We cannot place personal friendship above the interests of our cause.

Things have come to a sorry pass, comrades, if the only reason why we are called old Bolsheviks is that we are old. Old Bolsheviks are respected not because they are old but because they are eternally fresh, never-aging revolutionaries. If an old Bolshevik swerves from the path of the revolution or degenerates and fails politically, then, even if he is a hundred years old, he has no right to call himself an old Bolshevik; he has no right to demand the Party's respect.

Furthermore questions of personal friendship cannot be put on par with political questions for, as the saying goes, friendship is all very well but duty comes first. We all serve the working class and if the interests of personal friendship clash with the interests of the revolution the personal friendship must come second. As Bolsheviks we cannot have any other attitude.

I shall not touch either on the insinuations and veiled accusations of a personal nature that were contained in the speeches of Bukharin's opposition comrades. Evidently these comrades are attempting to cover up the underlying political basis of our disagreements with insinuations and equivocations. They want to substitute petty political scheming for politics. Tomsky's speech is especially noteworthy in this respect. His was the typical speech of a trade-unionist politician who attempts to substitute petty political scheming for politics. However that trick of theirs won't work.

Let's get down to business.

[...]

Bukharin's third mistake is on the question of the peasantry. As you know, this question is one of the most important questions of our policy. In the conditions prevailing in our country the peasantry consists of various social groups, namely, the poor peasants, the middle peasants and the kulaks. It's obvious that our attitude to these various groups cannot be the same. The poor peasant is the pillar of the working class, the middle peasant is the ally, the kulak is the class enemy. That's our attitude to these social groups. All this is clear and well known.

Bukharin sees the matter somewhat differently, however. His view of the peasantry blurs said differentiation, there are no social distinctions and what's left is a single drab patch called the countryside. According to him, the kulak is not a kulak and the middle peasant is not a middle peasant. The countryside is more-or-less poor. That's what he said in his speech here. "Can our kulak be really called a kulak?" he said. "Why, he is a pauper! And is our middle peasant really a middle peasant? Why, he is a pauper living on the verge of starvation." Obviously such a view of the peasantry is radically wrong, incompatible with Leninism.

Lenin said that household peasantry is the last capitalist class. Is that thesis correct? Yes, it's absolutely correct. Why is household peasantry the last capitalist class? Because the peasantry—out of the two main classes which conform our society—is the class whose economy is based on private property and whose output is meagre. Because family farming begets capitalists and cannot help begetting them constantly and continuously.

This fact settles the question of our Marxist attitude toward an alliance of the working class with the peasantry. We need not just any kind of alliance with the peasantry but solely an alliance that is based on the struggle against the capitalist elements of the peasantry.

As you see, Lenin's thesis on the last capitalist class being the peasantry not only does not contradict the idea of an alliance between the working class and the peasantry but, on the contrary, supplies the motivation for the alliance between the working class and most of the peasantry, aimed against capitalists in general and against the capitalist elements of the countryside in particular.

Lenin advanced this thesis in order to show that the alliance between the working class and the peasantry can be stable only if it is based on the struggle against those capitalist elements which a minority of the peasantry spawns in its midst.

Bukharin's mistake is not understanding and not accepting this simple concept. He erases the countryside's social hierarchy, loses sight of the kulaks and the poor peasants and wills an uniform mass of middle peasants.

This is doubtless a Right deviation on the part of Bukharin. It is the obverse of the "Left" Trotskyite deviation which sees only poor peasants and kulaks in a countryside devoid of middle peasants.

What is the difference between Trotskyism and Bukharin's group? The fact that Trotskyism is opposed to the policy of a stable alliance with the middle peasantry whereas Bukharin's group favours any kind of alliance with the whole peasantry. There is no need to show that both deviations are mistaken and equally worthless.

Leninism stands unquestionably for a stable alliance with the main mass of the peasantry, for an alliance with the middle peasants such that it reserves the leading role for the working class, consolidates the dictatorship of the proletariat and facilitates the abolition of classes.

[...]

I pass finally to the question of the rate of development of industry and of the new forms of the bond between town and country. This is one of our most important disagreements. Its importance lies in the fact that it holds all the strings of our practical disagreements regarding the economic policy of the Party.

What are the new forms of the bond, how do they shape our economic policy?

Firstly they imply that beside the old bond between town and country—whereby industry satisfied chiefly the personal needs of the peasant (cotton fabrics, footwear, and textiles in general, etc.)—we now have a new bond which must also satisfy the productive means of the peasant economy (agricultural machinery, tractors, improved seed, fertilizers, etc.).

Whereas earlier we satisfied chiefly the peasant's personal needs, hardly touching his means of production, presently, we must continue to satisfy his personal needs and additionally we must do our utmost to provide him with the latest means of production, tractors, fertilizers, etc., which bear directly on the reconstruction of our agriculture on a new technological basis.

As long as it was just a question of restoring agriculture and of the peasants cultivating the land formerly belonging to landlords and kulaks, we could be content with the old bond. But now, when it is a matter of reconstructing agriculture, that is not enough. Now we must go farther and help the peasantry to revamp agricultural production on the basis of new technology and collective toil.

Secondly, the new bond signifies that with the re-equipment of our industry we must simultaneously begin re-equipping our agriculture too. We are re-equipping and have already partially re-equipped our industry, placing it on a new technological footing, supplying it with brand new machinery and new better cadres. We are building new mills and factories, rebuilding and expanding old ones and we are modernizing the metallurgical, chemical and machine-manufacturing plants. On this basis new towns are springing up, new industrial centres multiplying and old ones expanding. On this basis the demand for foodstuffs and raw materials for the industrial sector is growing. But our agriculture still employs the old tilling tools of our forefathers—the antiquated useless or nearly useless ways of the old family farm.

Consider, for example, the fact that before the Revolution we had nearly 16 million peasant households, while now there are no less than 25 million. Does this not indicate that our agriculture is becoming more disperse and disjoint? And the norm for dispersed small farms is that they lack technology, machines, tractors and agronomy, these farms have small marketable surpluses.

Hence the insufficient output of foodstuffs for the market.

Hence the danger of a rift between town and country, between industry and agriculture.

Hence the need for increasing the rate of development of agriculture, bringing it up to the level of our industry.

And so, in order to eliminate this danger of a rift, we must begin to seriously refit agriculture on the basis of new technology. But in order to refit it we must gradually cluster the scattered family farms into big farms, into collective farms. We must build up our agriculture on the basis of collective toil, we must expand the collective farms, we must improve the old and new state farms, we must systematically contract farm workers on a massive scale in all the main branches of agriculture, we must set up machine-and-tractor stations to help peasants master the new technology and collectivize their labour. In a word, we must gradually migrate from scattered family farms to large-scale collective farms, for only large-scale socially-conducted farming can make full use of the scientific knowledge and modern equipment, and thus propel our agriculture forward in giant strides.

This does not mean of course that we can neglect the small family farm. Not at all. Poor- and middle-peasant farming plays a major role in supplying industry with food and raw materials and will continue to do so in the immediate future. Hence we must continue to assist the small family farms that have not yet joined a collective farm.

Withal the small family farm is no longer adequate. That's demonstrated by our difficulties procuring grain. That's why poor- and middle-peasant farming must be supplemented with the broadest possible creation and expansion of collective farms and state farms.

That's why we must erect a bridge between poor- and middle-peasant household farming and collective socially-conducted farming by means of mass-scale contracting, by means of machine-and-tractor stations and by the fullest promotion of co-operative communal life in order to help peasants migrate to collective farming.

Failing this it will be impossible to modernize agriculture to any extent. Failing this it will be impossible to solve the grain problem. Failing this it will be impossible to save the economically weaker strata of the peasantry from poverty and ruin.

[...]

I pass to the conclusions.

I submit the following proposals:

1) We must first of all condemn the views of Bukharin's group. We must condemn its views, expounded on its declarations and in the speeches of its representatives, and affirm that they are incompatible with the Party line and subscribe fully to the Right deviation.

2) We must condemn Bukharin's secret negotiations with Kamenev's group, a most flagrant expression of the disloyalty and factionalism of Bukharin's group.

3) We must condemn the resignation tactics of Bukharin and Tomsky as a gross violation of basic Party discipline.

4) Bukharin and Tomsky must be removed from their posts and warned that in the event of the slightest attempt at insubordination to the decisions of the Central Committee, it will be forced to exclude both of them from the Politburo.

5) We must take appropriate measures forbidding members and candidate members of the Politburo to deviate in any way—when speaking publicly—from the line of the Party and from the decisions of the Central Committee or its bodies.

6) We must take appropriate measures to ensure that press organs, both Party and Soviet, newspapers as well as periodicals, toe the line of the Party and the decisions of its leading bodies.

7) We must adopt special steps, including expulsion from the Central Committee or even from the Party, for anyone who attempts to breach the confidential nature of Party, Central Committee or Politburo decisions.

8) We must distribute the text of the resolution of the joint plenum of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission on intra-Party questions to all Party cells and to the delegates to the Sixteenth Party Conference without publishing said resolution in the press for the time being.

That, in my opinion, is the way out of this situation.

Some comrades insist that Bukharin and Tomsky should be expelled from the Politburo immediately. I diagree. In my opinion we can do without such an extreme measure for the time being.2

2. CONCERNING QUESTIONS OF AGRARIAN POLICY IN THE U.S.S.R.1

[...]

I pass finally to the class modifications in our country and the offensive of socialism against the capitalist elements of the countryside.

What characterizes the work of our Party during the past year is that we, as a Party, as the Soviet power:

a) have developed an offensive along the whole front against the capitalist elements of the countryside;

b) that this offensive, as you know, has yielded and continues to yield very appreciable positive results.

What does this mean? It means that we have passed from a policy of restricting the exploiting tendencies of the kulaks to the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class. It means that we have carried out and continue to carry out one of the decisive turns in our whole policy.

Until recently the Party adhered to a policy of restricting the exploiting tendencies of the kulaks. As you know, this policy was proclaimed as far back as the Eighth Party Congress. It was again proclaimed when the New Economic Policy was introduced and at the Eleventh Party Congress. We all remember Lenin's well-known letter (1922) where he once again returned to the need for pursuing this policy. Finally this policy was confirmed by the Fifteenth Congress of our Party. And we pursued it until recently.

Was this policy correct? Yes, it was absolutely correct at the time. Could we have undertaken a complete offensive against the kulaks some five or three years ago? Could we have counted on success then? No, we could not. It would have been most dangerous adventurism, very dangerous foolery, for we would certainly have failed and our debacle would have strengthened the kulaks. Why so? Because we did not yet have a wide network of state farms and collective farms which could bolster a determined offensive against the kulaks. At that time we could not yet replace the capitalist output of the kulaks with the socialist output of collective and state farms.

The Zinoviev-Trotsky opposition did its utmost in 1926-27 to impose upon the Party a policy of immediate offensive against the kulaks. The Party did not embark on that dangerous adventure for it knew that serious people cannot afford to play games with offensives. An offensive against the kulaks is a serious business and should not be confused with declamations against the kulaks nor with a policy of pinpricks which is what the Zinoviev-Trotsky opposition tried its utmost to impose on the Party. To launch an offensive against the kulaks means smashing them, eliminating them as a class. Unless we set ourselves these aims, the offensive is mere declamation, pinpricks, phrase-mongering, anything but a real Bolshevik offensive. To launch an offensive against the kulaks demands preparation and then punching them so hard that they can never stand up on their feet again. That's what we Bolsheviks call a real offensive. Could we have launched such an offensive some five or three years ago with any prospect of success? No, we could not.

Indeed the kulaks harvested over 600 million poods of grain in 1927, about 130 million they sold in urban districts. That was a substantial output to be reckoned with. How much did our collective farms and state farms produce at that time? About 80 million poods, 35 million of which were sent to the market (marketable grain).

Judge for yourselves, could we have replaced kulak output and kulak marketable grain in 1927 with the output and marketable grain of our collective farms and state farms? Obviously not.

What would a determined offensive against the kulaks under such conditionshave mean? Certain failure, raising the status of the kulaks and being left without grain. That's why we could not have embarked on a determined offensive against the kulaks then, despite the adventurist declamations of the Zinoviev-Trotsky opposition.

What is the situation today? Today we have adequate material foundation for striking at the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their output with the output of the collective and state farms. You know that the grain harvested on the collective farms and state farms in 1929 amounts to not less than 400 million poods (200 million poods short of the gross output of kulak farms in 1927). You also know that collective and state farms supplied more than 130 million poods of marketable grain in 1929 (i.e., more than the kulaks did in 1927). Lastly, you know that the gross grain output of the collective farms and state farms in 1930 will amount to not less than 900 million poods (i.e., more than the kulaks' gross output of 1927), and their supply of marketable grain will not be under than 400 million poods (i.e., incomparably more than what the kulaks supplied in 1927).

That's how matters stand with us now, comrades.

There you have the modification that has taken place in the economy of our country.

Presently we have the material base that enables us to replace kulak output with the output of collective and state farms. It's for this very reason that our determined offensive against the kulaks enjoys undeniable success.

That's how a real and determined offensive against the kulaks ought to be carried out, not merely with futile declamations against them.

That's why we have recently switched from a policy of restricting the exploiting tendencies of the kulaks to the policy of eliminating them as a class.

Well, and what about the policy of dekulakization? Can we permit dekulakization in areas of complete collectivization? This question is posed in various quarters.

A ridiculous question! We could not permit dekulakization as long as we were pursuing the policy of restricting the exploiting tendencies of the kulaks, as long as we were unable to go over to a determined offensive against them, as long as we were unable to replace kulak output with the output from the collective and state farms. At that time the policy of proscribing dekulakization was necessary and correct. But now it's a different story. Now we are able to carry on a determined offensive against the kulaks, to break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their output with the output of the collective and state farms.

Now dekulakization is being carried out by the poor and middle peasants themselves who are putting complete collectivization into practice. Now dekulakization in the areas of full collectivization is no longer just an administrative measure, it's an integral part of the creation and expansion of collective farms. Consequently it's now ridiculous and foolish to discourse at length on dekulakization. When the head's off no one mourns for the hair.

There is another question which seems no less ridiculous: whether kulaks should be permitted to join collective farms. Of course not, they are sworn enemies of the collective-farm movement.

[...]

On June 23, 1931, in a speech at a joint meeting of the Supreme Council of the National Economy with the People's Commissariat of Supply and with representatives of the Central Committee, Stalin boasted,Procurement is growing; we are exporting 1-1.5 million poods daily. I do not think that's enough. We need to raise the daily export quota (immediately) to at least 3-4 million poods. Otherwise we risk being left without our new metallurgical and machine-manufacturing plants (Avtozavod, Chelyabzavod, etc.). [...] In short, we need to accelerate our grain exports furiously.

In addition to food the authorities extorted family heirlooms through the Torgsin chain of stores. Starving people brought crosses, wedding rings and icons to exchange for the food they had had taken from them. Extortioned items were founded and sold abroad.We have overcome the grain difficulties, and not only overcome them, but we are exporting a quantity of grain abroad such as we have never exported before during the term of Soviet power.

The artificially-engineered mortality peaked in 1932–33. On January 7, 1933, commenting on the results of the First Five-Year Plan, Stalin enjoined the apparatchiks to keep a firm hand on the wheel,Despite a good harvest a number of productive regions in the Ukraine found themselves in a state of ruin and famine... Several tens of thousands of Ukrainian collective farmers are still wandering over the European part of the U.S.S.R., demoralizing our collective farms with their complaints and whining.

Paradoxically the impoverished collective-farm villages were the pillar of Stalin's achievements on the economic front. Even the grain procurements rose from 1929 to 1938 at almost no cost to the state. Whereas the Soviet government had between 1918 and 1921 confiscated fifteen million tons of grain through brute force and bloody reprisals, collective farming made it possible to harvest seventy million tons of grain between 1941 and 1945 without having to resort to food detachments.The Party has said directly that this matter will require serious sacrifices and that we must make them, openly and consciously, if we want to achieve our goal.

[...]

Establishing the strictest regime of austerity and accumulating the funds necessary to finance the industrialization of our country is the path that had to be taken in order to found our heavy industry.

3. THE FIGHT AGAINST THE KULAKS.

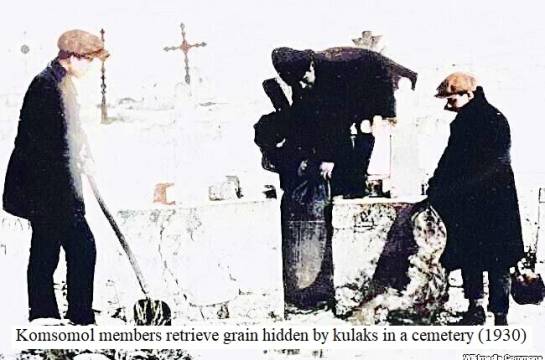

Earth (1930) |

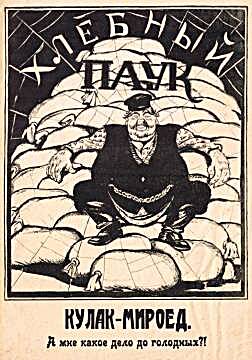

New Satyricon, 8, p. 4, 1918 |

4. REPLY TO COLLECTIVE-FARM COMRADES.

It's evident from the press that Stalin's article, "Dizzy with Success," and the decision adopted by the Central Committee on "The Fight Against Distortions of the Party Line in the Collective-Farm Movement" have evoked numerous comments among practical workers in the collective-farm movement. In this connection I have received lately a number of letters from collective-farm comrades asking for replies to the questions they raised. It was my duty to reply to these letters in private correspondence. But this proved impossible because more than half the letters had no return address (the senders forgot to write them). Yet the questions the letters touched upon are of immense political interest to all our comrades. Moreover I could not omit the comrades who forgot to write down their address. I am therefore obliged to reply to all the letters publicly, i.e., through the press, collating all the questions raised. I do this all the more readily since I have a direct decision of the Central Committee on this matter.

[...]

Ninth question. What is to be done with the kulaks?

Reply. So far we have spoken about the middle peasant. The middle peasant is an ally of the working class and our policy towards him must be friendly. As for the kulak, that's another matter. The kulak is an enemy of the Soviet regime. There is not and cannot be peace between him and us. Our policy toward the kulaks is to eliminate them as a class. That does not mean of course that we can eliminate them all at once. But it does mean that we shall endeavour to surround them and eliminate them.

Here is what Lenin says about the kulaks:

The kulaks are most bestial, brutal and savage exploiters who in the history of other countries have time and again restored the power of the landlords, tsars, priests and capitalists. The kulaks are more numerous than the landlords and capitalists. Nevertheless the kulaks are a minority of the people... These bloodsuckers have grown rich on the want suffered by the people during the war; they have raked in thousands and hundreds of thousands of rubles by raising the prices of grain and other products. These spiders have grown fat at the expense of the peasants who have been ruined by the war and at the expense of the hungry workers. These leeches have sucked the blood of the toilers and have grown ever richer the more the workers in cities and factories suffered hunger. These vampires have been and are gathering the landed estates into their hands; they keep on enslaving the poor peasants.

(Vol. XXIII, pp. 206-07)

We tolerated these bloodsuckers, spiders and vampires while pursuing a policy of restricting their exploiting tendencies. We tolerated them because we had nothing with which to replace kulak farming, kulak production. Now we are in a position to replace and more than replace their farming with our collective farms and state farms. There is no reason to tolerate these spiders and bloodsuckers any longer. To tolerate any loger these spiders and bloodsuckers who torch collective farms, who murder collective-farm leaders and who try to disrupt crop sowing would be going against the interests of the workers and the peasants.

Hence the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class must be pursued with all the persistence and consistency Bolsheviks are capable of.1

[...]

5. WILL THE STRUGGLE AGAINST THE KULAKS GO OVER THE TOP?

Chronicle of Half A Century. Year 1929 |

Chronicle of Half A Century. Year 1930 |

Source: Soviet films, plays and television programs. Four clips were extracted from this video for the year 1929 and subsequently spliced. Two clips were extracted from this video for the year 1930 and subsequently spliced.

Splicing was done with BeeCut.

Moscow: The U.S.S.R. during 1928 shut down three hundred and fifty-four Orthodox or Catholic churches, thirty-eight convents, fifty-nine synagogues, thirty-eight mosques and forty-three various other places of worship. This year it has already tagged for shutdown two hundred and fifty churches or chapels, etc.

Warsaw: News from Russia state that Tomsky the well-known Bolshevik has been deported to Monti, a town in Siberia. He was a member of the C.C.C.P. and president of the Soviet Council of Trade Unions. For some time now Tomsky had been opposing Stalin's dictatorship and sided with the Right Communists openly.

Moscow: Bukharin was deposed from the presidency of the Comintern. A similar fate befell another six moderate Party members.

Riga: President Stalin is gravely ill.

Helsingfors: Russian newspapers edited abroad assert that a newly created group, Komsomol Ruskaya, demands a preponderance of Russians in the Russian Communist Party in imitation of what the Georgian and Ukrainian communist parties do. The group advocates Stalin's demotion owing to his Georgian origin. Stalin has already jailed three hundred members of the group in the Solovetsky Monastery.

Riga: The news from Moscow state that Ordzhonikidze the president of the Central Control Commission and Stalin's right-arm man has declared that the struggle between the Soviets and the kulaks has entered a decisive phase. Izvestia the organ of the Soviet Government says in a lengthy article that the decisive battle is about to start,

Twelve years on, Soviet cities endure a dearth of nearly all agricultural products. This evokes derision in the enemies of the Soviets and in the Right Communists. Some years ago a kulak was merely a Shylok asking full payment for every pound of grain ceded, but this year he does not cede it for any kind of payment. The experience of the last weeks has shown that the problem of getting the kulaks' grain is not solved by sending manufactured goods to the towns.

The newspaper closes the article saying that this is evidently a political problem and that the Government is ready to accept the challenge of the kulaks and wage the final battle.

Berlin: Stalin ordered the arrest of Christian Rakovski, former Soviet Ambassador to Paris, who signed a document a short time ago and submitted it to the Government of Moscow. Stalin ordered his deportation to Barnaul in Siberia, situated three hundred and fifty kilometers south of Tomsk. Meanwhile Radek is back in a state of Soviet grace and writes articles against Trotsky and his supporters.

Stalin and Trotsky: The Soviet Government has decided to reject the petition of Trotsky and some of his supporters for permission to return to Russia and esteems that a general congress of the Russian Communist Party will have the final say on the matter.

Riga: The Soviet Government has paused its struggle against the German kulaks of the Volga Region. There are 1,200,000 German colonists in Russia whose model farms are the chief source of seeds, grain and cattle for the Volga Region. Six months ago Stalin launched a campaign against the German colonists and kulaks. Yesterday commissars of the National Soviet held a special meeting in Moscow and dropped the campaign to force Germans colonists into collective farms. The colonists had threatened to march on Moscow and quit farming altogether if Moscow did not cease sending agitators to their colonies. The commissars were also swayed by the German Government's adamant protests over the brutal treatment of the colonists and by the outrage vented in the German press over the past fifteen days as a result of the numerous interviews held with the five thousand Muscovite refugees currently living in Eastern Prussia.

Riga: Despite Bukharin's congratulatory note on the occasion of the dictator's birthday [December 18], Stalin sentenced him to internal exile. Bukharin left Moscow on Sunday morning (December 22) and headed to "Souchom" (Sochi) the small port on the Black Sea where Trotsky was first sent to exile three years ago.

Berlin: A book entitled, "Assassination, falsehood and provocation, the basis of Bolshevism," has just been published in Berlin. Its author is Vladimir Orlov, an examining magistrate of the Czarist Empire who fled abroad at the outbreak of the Revolution, but returned with a false passport and managed to infiltrate the Soviet secret police. Many pages of his book are devoted to Soviet political crimes, among them the murder of Krasin and "Jaroslawuski" (?). The author confirms Stalin's bias toward the use of poison as an assassination tool.

Moscow: Stalin received many compliments on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday. The shoemenders of Tiflis, where Stalin's father worked as a cobbler, sent a message to the head of the Government naming him the city's honorary cobbler.

The Soviets prosecute without compassion the war against the kulaks and five million men, women and children are the target of horrible persecution. Joseph Stalin delivered the watchword, "Liquidation of the kulaks as a class." And indeed that liquidation is being carried out radically and swiftly. The Kremlin's talk of war is not a rhetorical phrase. To date more than ten thousand families have been thrown out of home and country. Moreover the press informs daily about new districts deciding to expel the kulaks after seizing their land, cattle and farming implements.

[...]

And where will these millions of human beings go? No answer is forthcoming. War is war and those men are class enemies; their worst fate is not even being allowed to surrender ... The Kremlin's decree states it plainly: Kulaks will not be admitted to a collective farm under any pretext and any kulak who sneaks into one shall be thrown out immediately.

[...]

The Government has far more powerful forces than the kulaks' and the quick progress attained in the socialization of agriculture will compel hundreds of thousands of kulaks to emigrate in order to survive. Yes,—but whereto emigrate? Nobody knows.

[...]

A Roten Stern reporter said a short time ago that the current Soviet Government policy against the kulaks is the same one of old, only more severe. But this affirmation was refuted by Stalin who said that the current policy is not a continuation of the old one. Rather the goal now is the complete eradication of the kulak class in open combat.

Eugene LYONS

Berlin: Russian newspapers published abroad insert news from various places in Russia stating that Stalin's position is very shaky. The probable name of the next head of the Council of People's Commissars is being circulated already: Pyatakov, aforetime member of the Opposition, currently the Party's most popular figure.

Riga: News from Moscow state that great tension and division embroils the leading elements of the Party. It is known that at the last Party meeting Rykov wanted to table a project for improving the country's political environment, but Stalin the genuine dictator of the Communist Government opposed it vehemently. A violent discussion ensued and a heated Rykov took a shot at Stalin but missed. Rykov was detained immediately. The drama, whose subsequent evolution is unknown, riled the communist centers of Russia.

Warsaw: News from Riga state that Voroshilov the War Commissar resigned over differences of opinion with Stalin the dictator regarding collectivization. Rykov and Kamenev are also expected to resign from their posts.

Riga: The news from Moscow state that everything is ready for the Party Congress slated to open today in Moscow. The outcome is known following the statements of Voroshilov and Zinoviev, Stalin's main opponents. Voroshilov the War Commissar proclaimed yesterday his reconciliation with dictator Stalin. Zinoviev the former president of the Comintern, demoted in 1927, repentant, now back in Stalin's favour, wrote an eulogy of the dictator in Pravda, saying that the surest way of stirring a World Revolution is to make Russia a powerful industrial power capable of selling all kinds of goods at the lowest prices, flooding the global market, raising the unemployment rate of capitalist countries and ensuring the outbreak of a World Revolution.

Riga: Pravda announces that Soviet construction of huge tractor factories—the year's outstanding Bolshevik accomplishment—is complete. Dictator Stalin sent a telegram of thanks to the American engineers and mechanics who supervised the construction. He also hailed the Soviet technicians and workers who did the actual work, telling them that "the fifty thousand tractors to be manufactured yearly can be likened to fifty thousand bombs, another accessory to obliterate the capitalist world." But Soviet authorities already foresee hitches because raw materials and skilled mechanics are wanting and because certain components will be manufactured in auxiliary factories.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |