1. THE ECONOMIC SITUATION OF THE SOVIET UNION AND THE POLICY OF THE PARTY.

Comrades, permit me to begin my report.

There were four items on the agenda of the April plenum of the Central Committee of our Party.1

The first item was the economic situation of our country and the economic policy of our Party.

The second item was the reorganization of our grain procurement agencies with a view to making them simpler and cheaper.

The third item was the plan of work of the Political Bureau of our Central Committee and of the plenum of the Central Committee for 1926 from the viewpoint of working out key questions of our economic construction.

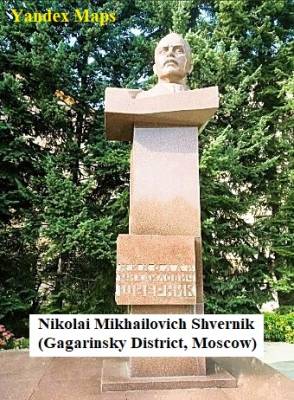

The fourth item was the replacement of Yevdokimov 2 as Secretary of the Central Committee with another candidate, Comrade Shvernik.3

[...]

But accumulation [net state revenues] is not the whole of the problem by any means. We must also know how to spend the accumulated reserves wisely and thriftily so that not a single kopek of the people's wealth is wasted and the funds get used for industrializing our country. Unless these conditions are met, we shall run the risk of [misusing] our accumulated funds...

[...]

That is why correct and intelligent industrial planning is an indispensable condition for the expedient use of accumulations.

It's necessary in second place to shrink and simplify our state and co-operative apparatus, our state- and self-financed institutions from top to bottom, to place them on a sounder footing and to make them economical. Glutted departments and the unparalleled extravagance of our administrative bodies have become a byword. It was not without reason that Lenin asserted scores and hundreds of times that our unwieldy and costly state apparatus was too great a burden on the workers and peasants and that it had to be reduced and made cheaper at all costs and by every means available. It's high time to set about this in earnest, in a Bolshevik way, and to establish a regime of the strictest economy.

(Applause)

[...]

It's necessary in third place to wage a determined struggle against every kind of extravagance in our administrative bodies or in everyday life, and against that criminal disregard for the people's wealth or state reserves which has been conspicuous of late. We see prevailing now among us a regular riot, an orgy, of all kinds of fêtes, celebration meetings, jubilees, unveiling of monuments and the like. Scores and hundreds of thousands of rubles are squandered on these "affairs." There is such a crowd of celebrities of all kinds to be fêted and such a multitude of lovers of celebrations, so staggering a readiness to celebrate every kind of anniversary (semi-annual, annual, biennial and so on) that truly tens of millions of rubles are needed to satisfy the demand.

Comrades, we must put a stop to this profligacy unworthy of Communists. It's high time to understand that with the needs of industry to provide for, and faced with such facts as the mass of unemployed and of homeless children, we cannot tolerate and have no right to tolerate this profligacy and this orgy of squandering.

Most noteworthy of all is that a thriftier attitude toward state funds is sometimes observed among non-Party rather than Party people. A Communist squanders with greater boldness and proclivity. To him it means nothing to distribute money allowances to a batch of his employees and call these gifts bonuses. To him it means nothing to overstep, evade or break the law. Non-Party people are more cautious and restrained in this respect. The reason presumably is that some Communists are wont to regard the law, the state and such matters as a family affair.

(Laughter)

This explains why some Communists sometimes do not demur to intrude like pigs (pardon the expression, comrades) in the state's vegetable garden and snatch what they can—or to show off their generosity at the expense of the state.

(Laughter)

This scandalous state of affairs must be stopped, comrades. We must launch a determined struggle against profligacy and squandering in our administrative bodies and in everyday life if we sincerely wish to husband our accumulations for the needs of industry.

It's necessary in fourth place to conduct a systematic struggle against theft, against what is known as "carefree" theft in our state bodies, co-operatives, trade unions, etc. There is the timid and surreptitious theft and there is the brazen or "carefree" theft, as the press calls it.

I recently read an item by Okunev in Komsomolskaya Pravda about "carefree" theft. There was, it seems, a foppish young fellow with moustache who carried on his "carefree" theft in one of our institutions. He stole systematically, incessantly, always without mishap. The noteworthy thing is not the thief as much as the fact that the people around him who knew that he was a thief not only did nothing to stop him but, on the contrary, tended to pat him on the back and praise his dexterity. So the thief became a sort of folk hero. That's what deserves attention, comrades, and it's the most dangerous thing of all. When a spy or a traitor is caught, there are no bounds to the public indignation demanding that he be shot. But when a thief pilfers state property in plain sight the people around him just smile good-naturedly and pat him on the back. Yet it's obvious that someone who steals the people's wealth and undermines the interests of the national economy is no better, if not worse, than a spy or a traitor. Finally, of course, this fellow—the fop with moustache—was arrested. But what does the arrest of one "carefree" thief entail? There are hundreds and thousands of them. You cannot get rid of them all with the help of the G.P.U. A more important and effective measure is required here and it consists in surrounding such petty thieves with an atmosphere of moral ostracism and public detestation, in launching such a campaign and creating a moral atmosphere among the workers and peasants that decreases the likelihood of pilfering and makes life difficult or impossible for looters and pilferers of the people's wealth, whether "carefree" or not. The task is to shield our accumulations from misappropriation by combating theft.

It is necessary, lastly, to conduct a campaign to put a stop to absenteeism at mills and factories, to raise the productivity of labour and to heighten discipline in our enterprises. Tens and hundreds of thousands of man-days are lost to industry owing to absenteeism. Hundreds of thousands and millions of rubles are lost as a result, to the detriment of our industry. We shall not be able to improve our industry, we shall not be able to raise wages, if absenteeism is not curtailed, if labour productivity stagnates. It must be explained to workers, especially to recent arrivals at mills and factories, that absenteeism and stagnant productivity are a detriment to the common cause, to the entire working class and to our industry.

The task is to combat absenteeism and to fight for higher productivity in the interests of our industry, in the interests of the working class as a whole.

Such are the ways and means that must be adopted to protect our accumulations and reserves from being misspent, to ensure that they are used for the industrialization of our country.

I have spoken of the road to industrialization. I have talked about how to accumulate reserves for greater industrialization. I have outlined lastly how accumulations should be used rationally for the needs of industry. But all that, comrades, is not enough. If the Party's directive concerning the industrialization of our country is to be implemented it is necessary, over and above all that, to create cadres of new people, cadres of new builders of industry.

No task—and especially so great a task as the industrialization of our country—can be accomplished without human beings, without new people, without cadres of new builders. Formerly during the Civil War we were especially in need of commanding cadres for building the Army and waging war: regimental, brigade, divisional and corps commanders. Without those new commanders who had come up through the ranks and risen by reason of their ability we could not have built up an Army or defeated our numerous enemies. Those new commanders together with the general support of workers and peasants, of course, saved our Army and our country in those days. But we are presently in the period of building up our industry. We have now passed from Civil War fronts to the industrial front. Accordingly we need new commanding cadres for industry now, capable directors of mills and factories, competent executives of trusts, efficient trade managers, intelligent planners of industrial development. Presently we have to create new regimental, brigade, divisional and corps commanders for the economy, for the industry. Without such people we shall not be able to take one step forward.

[...]

It has become customary of late to abuse business executives on charges of moral corruption and there is often a proclivity to generalize individual faults and blame all business executives. Anyone so disposed can come along, kick a business executive and accuse him of all the mortal sins. Comrades, that's a bad habit. It must be dropped once and for all. It must be realized that every family has a black sheep. It must be realized that our country's industrialization and the promotion of new cadres of industrial builders does not require scourging but rendering our business executives every support. Our business executives must be enveloped by an atmosphere of confidence and support, they must be helped to mould new industrial builders, and the post of industrial builder must become a post of honour in socialist construction. Those are the lines along which our Party organizations must now work.

Such are the immediate tasks confronting us in connection with the road to the industrialization of our country.

Can these tasks be accomplished without the direct assistance and support of the working class? No, they cannot. Improving our industry, raising its productivity, creating new cadres of industrial builders, conducting socialist accumulation rightly, using accumulations sensibly for the needs of industry, establishing a regime of the strictest economy, tightening up the state apparatus to make it operate cheaply and honestly, purging it of the dross and filth that adhered to it during our work of construction, waging a systematic struggle against thieves and squanderers of state property are tasks which no party can cope with without direct and systematic support of the vast masses of the working class. Hence the task is to draw the vast masses of non-Party workers into our constructive work. Every worker, every honest peasant must assist the Party and the Government in putting a regime of thrift into effect, in combating misappropriation and dissipation of state reserves, in getting rid of thieves and swindlers, no matter what disguise they wear, and in making our state apparatus healthier and cheaper.

Inestimable service in this respect could be rendered by production conferences. There was a time when production conferences were very much in vogue. Now we don't hear about them somehow. That's a great mistake, comrades. The production conferences must be revived at all costs. It is not only minor questions, for instance of hygiene, that must be put before them. Their programme must be made broader and more comprehensive. The principal questions of industry building must be raised. Only in that way is it possible to increase the activity of the vast masses of the working class and to make them conscious participants in industry building.4

[...]

2. REPLY TO THE GREETINGS OF THE WORKERS OF THE CHIEF RAILWAY WORKSHOPS IN TIFLIS.1

Comrades, permit me first of all to tender my comradely thanks for the greetings conveyed to me here by the representatives of the workers.

I must say in all conscience, comrades, that I do not deserve a good half of the flattering statements that have been said here about me. I am, it appears, a hero of the October Revolution, the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the leader of the Communist International, a legendary warrior-knight and all the rest of it. That's absurd, comrades, and quite an unnecessary exaggeration. It's the sort of thing usually said at the graveside of a departed revolutionary. But I have no intention of dying yet.

I must therefore give a true picture of what I was formerly and to whom I owe my current standing in our Party.

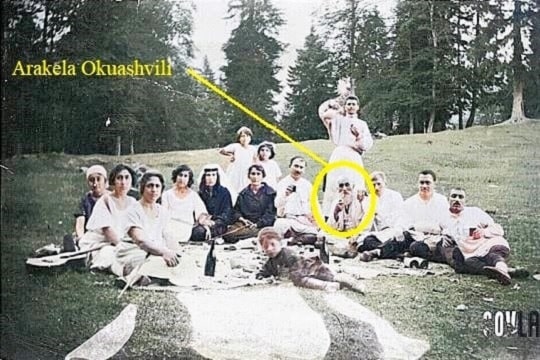

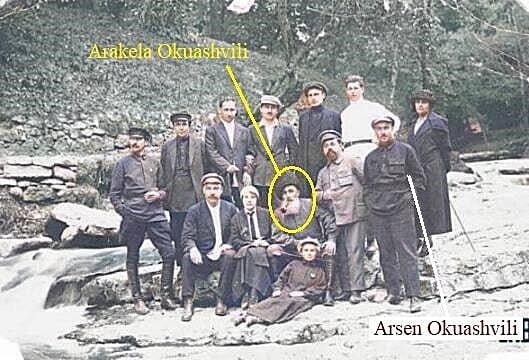

Comrade Arakel 1 said here that he regarded himself as one of my teachers in the old days and saw me as his pupil. That's perfectly true, comrades.2

I really was and still am a pupil of the advanced workers of the Tiflis railway workshops. Let me turn back to the past.

I recall the year 1898 when I was first put in charge of a study circle of workers from the railway workshops. That was some twenty-eight years ago. I recall the days when at the home of Comrade Sturua and in the presence of Djibladze (he was also one of my teachers at that time), Chodrishvili, Chkheidze, Bochorishvili, Ninua and other advanced Tiflis workers I received my first lessons in practical work. Compared with these comrades I was quite a young man. I may have been a little better-read than many of them but as a practical worker I was unquestionably a novice. It was here, among these comrades, that I received my first baptism of revolutionary struggle. It was here, among these comrades, that I became an apprentice in the art of revolution. As you see, my first teachers were Tiflis workers.

Permit me to tender them my sincere comradely thanks.

(Applause)

I recall, further, the years 1907-09 when, by the will of the Party, I was transferred to work in Baku. Three years of revolutionary activity among oil industry workers steeled me as a practical fighter and as a local practical leader. Association with such advanced workers in Baku as Vatsek, Saratovets, Fioletov and others, on the one hand, and the storm of acute conflicts between the workers and the oil owners, on the other, taught me for the first time how to lead large masses of workers. Thus there in Baku I received my second baptism of revolutionary struggle. There I became a journeyman in the art of revolution.

Permit me to tender my sincere comradely thanks to my Baku teachers.

(Applause)

Lastly I recall the year 1917 when, by the will of the Party, after wandering from one prison or place of exile to another I was transferred to Leningrad. There in the society of Russian workers and in direct contact with Comrade Lenin the great teacher of the proletarians of all countries, in the storm of mighty clashes between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, in the environment of the imperialist war, I first learned how to be a leader of the great Party of the working class. There in the society of Russian workers—the liberators of oppressed peoples and the pioneers of the proletarian struggle of all countries and all peoples—I received my third baptism of revolutionary struggle. There, in Russia, under Lenin's guidance, I became a master workman in the art of revolution.

Permit me to tender my sincere comradely thanks to my Russian teachers and to bow my head in homage to the memory of my great teacher, Lenin.

(Applause)

From the rank of an apprentice (Tiflis) to the rank of a journeyman (Baku) and then to the rank of a master workman of our revolution (Leningrad) was the revolutionary apprenticeship curriculum I coursed, comrades.

That's the true picture of what I was and what I have become, comrades, if one is to speak without exaggeration and in all conscience.

(Applause rising to a stormy ovation)

Date of birth: November 12, 1865.

Date of birth: November 12, 1865.

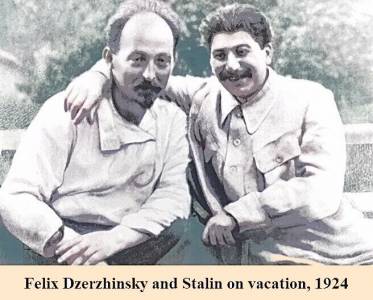

3. F. DZERZHINSKY.

First Frunze, now Dzerzhinsky.

The old Leninist Guard has lost another of its finest leaders and fighters. The Party has sustained another irreparable loss.

Standing now at Comrade Dzerzhinsky's bier and looking back at his whole life's journey—imprisonment, penal servitude and exile, the Extraordinary Commission for combating Counter-Revolution, the restoration of the ruined transport system, the building of our young socialist industry—one feels that the defining trait of his seething life was a FIERY ARDOUR.

The October Revolution allotted him an exacting post, head of the Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution. No name was more hated by the bourgeoisie than Dzerzhinsky`s for he repelled the blows of the enemies of the proletarian revolution with a hand of steel. "The terror of the bourgeoisie" was the name given to Comrade Felix Dzerzhinsky in those days.1,2

When the "period of peace" started, Comrade Dzerzhinsky continued his seething activities. He applied his burning energy to putting the dislocated transport system in order. Subsequently as Chairman of the Supreme Council of the National Economy, he worked with equal zeal to build up our industry. Never resting, never shunning the roughest task, gallantly contending with difficulties and overcoming them, and dedicating all his strength and energy to the task entrusted to him by the Party, he burnt out his life working in the interests of the proletariat and for the victory of communism.

Farewell, hero of October! Farewell, loyal son of the Party!

Farewell, builder of the unity and might of our Party!

J. Stalin

July 22, 1926 3

4. FIFTEENTH ALL-UNION CONFERENCE OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY.1 REPLY TO THE DISCUSSION ON THE REPORT ON "THE SOCIAL-DEMOCRATIC DEVIATION IN OUR PARTY."

[...]

What are the conclusions, the results, of our intra-Party struggle?

I have here the document of September 1926 signed by Trotsky. This document is remarkable for the fact that there is in it something in the nature of an attempt to anticipate the results of the intra-Party struggle, something in the nature of an attempt to prophesy, to outline the prospects of our intra-Party struggle. This document states:

The United Opposition demonstrated in April and July and will demonstrate in October that the harmony of its views merely grows stronger under the influence of the gross and disloyal persecution it is being subjected to, and the Party will come to realize that only on the basis of the views of the United Opposition is there a way out of the current severe crisis.

As you see, this is almost a prediction.

(A voice: "Yes, almost!")

It's almost a prophecy of the genuine Marxist variety, a forecast for a full two months ahead.

(Laughter)

Of course, there's a slight exaggeration in it.

(Laughter)

It speaks, for instance, of the present severe crisis in our Party. But we, thank God, are alive and flourishing and haven't even noticed any crisis. There is of course something in the nature of a crisis—only not in the Party but in a certain faction known as the Opposition bloc. But, after all, a crisis in a tiny faction cannot be represented as a crisis in a Party a million strong.

Trotsky's document further states that the Opposition bloc is getting stronger and will grow still stronger in future. I think there is a slight exaggeration here too.

(Laughter)

The fact can not be denied that the Opposition bloc is disintegrating, that its best elements are breaking away, that it is suffocating in its own internal contradictions. Is it not a fact, for instance, that Comrade Krupskaya is deserting the Opposition bloc?

(Stormy applause)

Is that accidental?

Trotsky's document says, lastly, that only on the basis of the United Opposition's views is there a way out of the current crisis. I think that here too Trotsky is exaggerating slightly.

(Laughter)

The oppositionists cannot but know that the Party has become united and firmly welded not on the basis of the Opposition bloc's views but in a struggle against them, on the basis of the socialist prospects of our constructive work. The puffery in Trotsky's document is glaring.

But if we discard all the hype in Trotsky's document it does look, comrades, as if nothing remains of his prophecy.

(General laughter)

As you see, the conclusion is the obverse of Trotsky's prophecy.

I am concluding, comrades.

Zinoviev once boasted that he knew how to put his ear to the ground...

(Laughter)

and that when he put his ear to the ground he could hear the footsteps of History. It may very well be that this is actually so. But one thing is clear and it's that Zinoviev, though able to put his ear to the ground and hear History's footsteps, fails to hear certain "trifles" sometimes. Maybe the Opposition is actually able to put its ear to the ground and hear such wonderful things as the footsteps of History, but one has to admit that, while hearing such wonders, it did not hear some "trifles" such as that the Party has long ago spurned it and that the Opposition is on the rocks. That they have failed to hear.

(Voices: "Quite right!")

What follows from this? Something is obviously wrong with the Opposition's ears.

(Laughter)

Hence my advice: worthy oppositionists, have your ears checked!

(Stormy and prolonged applause)

(The delegates rise from their seats, applauding as Comrade Stalin leaves the rostrum)

58. THE RED TYRANTS FIGHT AMONG THEMSELVES.

The root of the policy promoted at the last Congress of the Russian Communist Party [the Fourteenth Party Congress of December 18-31, 1925] responsible for the split between Zinoviev (Petrograd faction) and Stalin, Bukharin, Rykov, etc. (Moscow faction), is none other than the critical financial situation that Russian farmers have put the Soviets in.

The crisis originates in the farmers' refusal to sell their wheat to the Soviet Government, thus depriving it of export revenue. Their refusal disables the Soviets' economic projects which hinged precisely on the export of wheat.

The decay of the Russian industry, unable to produce in quantity or quality the goods the country needs, forces the Soviet Government to buy those goods abroad. This makes Russia dependent on capitalist states, and to obviate this plight the Soviets endeavour to revive their industry and round out their economy. It is necessary to multiply and update broken-down machinery and outdated technical manuals. Most factories stand idle because their equipment is obsolete and incomplete. Thus new equipment and documentation must be purchased abroad.

To raise agricultural output it is necessary to replenish the inventory depleted in the heavy fighting that beset the countryside during the first years of socialism. This inventory must also be purchased abroad.

Under the current political, social and economic situation of Russia, the only guarantee the Soviet Government can offer a foreign supplier is the sale of its natural resources. That's why as soon as the government realized that the 1925 cereal crop was a bountiful one—the best since 1913—it began making purchases abroad guaranteeing short-term payment with the sale of wheat; but the government did not tally the farmers' open and resolute opposition to Soviet price fixing.

It's not surprising then that since crops, the harvest of wheat paramount, constitute the most important item in the Soviet export forecast for the exercise that began on October 1, the setback made the whole forecast fizzle out.

To understand the attitude of Russian farmers one must explain the country's current agricultural policy.

In the early days of Soviet power the agricultural policy stamped on the countryside was "the class struggle"; but it soon became evident that a state of war in the countryside, or the collectivization of the land, ruined the country's chief economic asset, agriculture. Thence the application of the "New Economic Policy" (N.E.P.) which tolerates private ownership of the land (temporarily, say the Soviets). In this way the traditional class structure of the countryside was preserved: poor peasants, middle peasants and kulaks or rich peasants.

Under the N.E.P. the kulaks enjoy economic freedom and are joined by a new bourgeoisie, expert technical specialists and top bureaucrats well acquainted with the international capitalist coterie, as Zinoviev admitted in the recent Conference and Congress.

As matters stand—chronically poor harvests and awareness that hoards of grain were seized by the government as "landed property was socialized"—the peasant protected by the N.E.P. wishes to retain a portion of his good harvest as insurance against the hunger he suffered in the past.

Moreover the Russian farmer expected that his good harvest would at last enable him to purchase the manufactured goods he needs. He took his wheat to the official market only to find that Soviet industry and commerce could not satisfy his demand, and very soon speculators feigned a complete sellout of their merchandise and directed customers to faraway markets where prices were inflated: the official trading scheme flopped.

And curiously enough the Soviet Government did not resort to its usual coercive measures or force the farmer to sell at the government's fixed price. It did not dare because under the N.E.P. the farmer has the right to keep a portion of his wheat. Nor did it use the Red Army to have its way because the Army, aforetime made up entirely of workers, is now 90% composed of peasants.

In the beginning the Soviet Government forced the farmer to give up everything he owned to the State "god"; but today the farmers not only don't give the State their wheat, they don't even sell it at the price fixed by the authorities. How much has Russian communism receded!

S. DE P.

Madrid: A dispatch from Berlin states that the German Government is negotiating with Russia the sale of a huge manufacturing plant of locomotives. The sale price is sixty million gold rubles.

Often people ask themselves, "Who governs Russia?" The reply was easy when Lenin was alive, for the prestige of Vladimir Ilych Ulianov was so great among his comrades that no other name dared to dispute his hold on Power. And even among ordinary people a legend had been woven of Lenin as the sole true-blue Russian in a bevy of Bolsheviks from other nationalities (Jews, Poles, Ukrainians, Caucasians, Latvians), a Lenin who advocated the interests of the peasant population and argued their needs. In short, Lenin seemed to many Russians to be a sort of new Tsar, good and humane, but surrounded by evil counsellors.

The Power struggle among his lieutenants began after his death. Leo Trotsky was the best known Bolshevik figure abroad, but Trotsky is Jewish, and besides, has many enemies owing to his haughty and caustic character. Trotsky was set aside, then, and Lenin's successor in the post of President of the Council of People's Commissars was Alexei Rykov, unknown figure in the West.

Does this mean that Rykov governs Russia? Not at all. The Secretary-General of the Bolshevik Party, Stalin, pseudonym of the Georgian Dzhugashvili, is much stronger than him. Stalin's rank was unveiled during the "Trotsky affair" when on the occasion of the publication of a book written by Trotsky about the preparation for and execution of the Bolshevik coup d'état (November 1917) severe measures were taken against the author. Trotsky was compelled to cede the leadership of the Army and the Navy and was banished to Tiflis in the Caucasus.

The victor besides Stalin that day was Grigory Zinoviev the Secretary-General of the Third International and the dictator of Leningrad (Petrograd). Foreign observers may have presumed that Zinoviev was the true arbiter of the situation, even more than Stalin, and of course more than Kalinin the president of the Central Executive Committee and in this attribution president of the Federal Republic. In actual fact the least important figures today in Russia are the two presidents: Kalinin and Rykov.

Withal Zinoviev's triumph did not prove long-lasting. As soon as he took it upon himself to mount an opposition to Moscow's "moderate" policy he found himself in the minority and today we can say he is hardly influential. Very adroitly Stalin shoved Trotsky to the background with Zinoviev's assistance.

May it be asserted then that Stalin is the one who governs Russia?

No. The true arbiter of the situation is a man who is mentioned little: Felix Dzerzhinsky. Dzerzhinsky is of Polish origin, a quiet man, cold, reserved, but extremely dynamic, often cruel, one of those revolutionary types whom Anatole France portrays in his novel, "The Gods are Athirst."

After Uritsky's assassination he was appointed head of the Cheka, i.e., of the secret political police which surveilled even the People's Commissars themselves and the very leaders of the Party. The Cheka does not exist today, better said: it has been supplanted by the so-called G.P.U. which continues carrying out the same terrible deeds under another name.

As uncontested head of the G.P.U. Dzerzhinsky is the most feared man in Russia; everyone essays to have good relations with him. He hardly ever meddles in Party politics, but in regard to State affairs he demands absolute obedience from everybody. And beyond being the head of the G.P.U. he is also the head of the Economy Department with a hand in every ministry, ruling on the nationalization of commerce and on its freedom, War Communism and the return to private business.

It has often been said that "Bolshevism is Tsarism inside out"; in effect today, as aforetime, the will of one man surrounded by a small General Staff governs the destinies of Russia.

JUAN DE VACZ.

Riga: Telegrams from Russia outline the prevailing unrest. The reports insist that the situation is grave and that there occurred disorders and uprisings in Leningrad, Moscow, Ukraine and the Black Sea. Apparently the Mensheviks lead the agitation.

Wildwood winds arrive from Russia. According to what the Agencies transmit, a revolution has broken out in Petrograd and Kronstadt. The telegrams add that the Black Sea Fleet has rebelled and occupied Kherson.

The rebellious movement has been instigated by the supporters of Zinoviev and Trotsky, both of whom have summarily declared themselves in opposition to Stalin. Soviet agencies refute the news; but since the official truth does not alway spotlight truth, for the sake of informing our readers we admit both sources and let time reveal what there may be of truth in each.

What is certain is that following the death of tyrant Lenin rivalry among the dictators stirred up very violent antagonisms. Firstly Zinoviev and Stalin connived to eliminate Trotsky.

Presently, if the dispatches do not lie, Trotsky and Zinoviev have joined forces to overthrow Stalin. For some time the standing of Zinoviev and company was chipped away gradually, Zinovievists were excluded from leading organs and not a few deported or even jailed.

Withal Zinoviev did not lay down his weapons despite a formal repentance with a promise to drop all whims of mounting an opposition.

Unable to resort to legal means of propaganda he resorted to a clandestine campaign against Stalin and the other holders of Power. He became a conspirator, a revolutionary inside the Communist Party, working to undermine the position of the victors. Evidently we can not foretell whether or not he will fulfill his goals. But we dare indeed to affirm that the Red tyrants are in a fracas and that a regime which rests not on reason, nor on conscience, but on brute force and terror, necessarily must finish worse than it began—if there is anything worse than the Bolshevik mostrosities already committed. Nothing violent lasts long. Reaction eventually sets in and overturns; we have no doubt about that.

Bucarest: Considerable unrest spreads across Russia. The Soviet Government has declared a country-wide state of siege. The petit bourgeoisie and the peasants have mostly gone over to the insurgents. Peasants refuse to obey the governmental order to surrender 55% of their harvest. Railway traffic has halted in several regions. Railway employees were militarized. Wine and alcohol retail stores are shut. Part of the North Sea Fleet (?) mutinied and occupied Kertche (Crimea) "Keiron" (?) and Sevastopol.

Riga: Russian socialist press reports state that the mobilization by workers is vigorous in all the industrial centers. Great excitement drove the "unemployed" to march through the streets of Odessa, Kiev, Poltava and Ekaterinoslav. More than twenty thousand workers took to the streets of Kiev demanding bread and work. According to Labour Commissariat statistics there are currently 1,200,000 men without work.

Riga: The Baltic Fleet has left Krondstat abruptly, destination unknown. Top Bolshevik leaders are said to be on some cruisers, for example Kamenev aboard the cruiser Marat.

The great loser of the Power struggle in Russia is known by the name of Grigory Zinoviev, and no one knows his real surname. Some say it is Apfelbaum, others Radomilsky. What is known is that he was born of Jewish parents like so many other figures of Bolshevism: Trotsky, Kamenev, Sokolnikov, Scheinman, et cetera.

He was born in 1883 in Novomirs-Gorodsk. His life resembled that of many Russian revolutionaries: underground propaganda, detention, sentence, imprisonment, flight abroad.

Zinoviev lived abroad from 1908 and for a spell was Lenin's secretary, a circumstance that sealed his career. He wrote a work with his teacher entitled, "War and Socialism," which expounds the defeatist doctrine of Bolshevism. In 1917 he returned with Lenin across Germany to Russia.

In November's Communist Revolution he adopted a rather passive attitude because he esteemed it was not the right time to grab Power. In effect, at that time the Bolsheviks did not have a majority anywhere, not even in the Soviets of Workers, Peasants and Soldiers. However Lenin and Trotsky demanded full Power for the Bolshevik Party. As can be gauged, Zinoviev was initially less radical than his teacher and stood in open opposition to Lenin's revolutionary tactic. Yet Lenin forgave his former secretary all and when the central Government was transferred to Moscow Zinoviev tarried in Petrograd (later Leningrad) with two posts: almighty dictator and head of the Third International.

Zinoviev is of average height, barely obese, a type between Jewish banker and Roman emperor. He has abundant frizzy hair, black eyes and a small mouth slightly askew.

His personality holds little appeal, impulsive, vain, braggart. He does not owe his career to his talent but to Lenin's protection and to having been judged after Lenin's death as the best repository and interpreter of his legacy. For some time he formed with Stalin and Kamenev the famous "troika" (triumvirate) that waged war on Trotsky's "Bonapartism" and procured his removal from Power.

The victory of Zinoviev over Trotsky proved short-lived, Stalin undertook to break up the triumvirate and acquire Power for himself. His friends and accomplices—professors Bukharin, "Stechky" (?) and "Slyepkof" (?)—attacked the Zinovievite interpretation of the Teacher's doctrine vigorously and exposed the Petrograd dictator's intellectual emptiness. Every day Zinoviev was outstripped more and more. Finally at the Sixteenth Party Congress (December 1925) the opposition he captained was crushed by the governmental majority.

Zinoviev's friends—Kamenev, Sokolnikov, Lashevich and others—were completely driven away from Power. Zinoviev keeps his prominent role in the Third International but only until the next Congress.

We don't exaggerate when we say that Zinoviev is politically defunct. Trotsky had an important group of intellectuals behind him, he had (and still has) enthusiastic supporters in the Red Army which was, to a certain degree, his own creation, and had the reputation of being a fearless leader during the most critical days of the Revolution. There is nothing and no one behind Zinoviev, just a coterie girthed to him for material benefits. Zinoviev's elimination will not weaken the Bolshevik Party at all.

The great asset of the Party is its nearly mystical faith in Leninism, which lends it renewed enthusiasm to face and overcome the greatest difficulties every time. And the new Bolshevik General Staff that seeking to personify this Leninism is Stalin, Bukharin, Kuybyshev and "Rudzatak" (?).1

JUAN DE VACZ.

Russian bolshevism had hardly conquered power when it confiscated, by brute force of course, the factories and the land, and monopolized the industry and the commerce. Russia could gaze upon the apotheosis of the marxist ideal. Socialism had triumphed all along the line.

The Soviets had every asset of the nation at their disposal and they gagged despotically aught that could mar the triumphal march of their theories.

The press that would not endorse their ideals was banned; institutions that offered the least resistance were dissolved; priests and religious people were persecuted with blood and fire, every one who might preach doctrines contrary to the teachings of Marx. Never since the day he published his peculiar economic systems had any nation been so prone to the victory of socialism.

All the privileges of authority were in their hands; nothing in Russia obstructed.

Not a few weaklings came to imagine that socialism, according to the marxist concept, would triumph decisively in the Muscovite country and would even spread to other peoples.

We have predicted the failure of marxism repeatedly—our readers will remember—and this because the economic theory of Marx carries in its bosom the seeds of its own debacle.

Marxist theory suppresses every incentive of the workingman: the incentive beyond the grave because the materialist concept of History proposed by Marx denies reward or punishment in an afterlife it rejects; and the incentive here and now because the worker does not fatigue for his own profit but for the community's, and such self-denial Marx and all his partisans will never instill in man's heart whose innate self-interest only religious faith can smother.

That's why just as libertine socialism has foundered in Russia it will founder elsewhere however many times it's tried anew.

The peasants were granted ownership of the lands they tilled for a certain number of years in the understanding that the State retained the absolute ownership of the land. In view of this lingering uncertainty, the peasant opted to till only the plot of land that would afford him and his family the requisite sustenance. Agricultural production plummeted to extraordinary levels that brought death by starvation to millions of Russians.

Agricultural production increased with a cession of the land for a certain number of years but not enough to satisfy all the needs of the Muscovite country because when the Soviets attempted to confiscate the surplus the peasantry defended itself with the force of arms. This impelled Lenin to deal a second mortal blow to marxism in 1921 by authorizing private trading in Russia.

It was not enough; Soviet monopoly on foreign trade depreciated the goods produced by Muscovite workers and profited only the people who held Power. This is logical, production levels fell when the incentive to produce was partly taken away.

And presently the telegraph informs us that the Russian Supreme Council of the National Economy is, on Stalin's initiative, preparing a decree to legalize private and independent trade between Muscovites and the rest of the world.

The weaklings can rest easy upon these news. Only through deceit or sheer stupidity can marxist theories continue to spread, given that Russian socialism has failed conclusively with the authorization of private commerce, toppling the last stronghold.

Elías OLMOS.

Tarín has devoted a well-rounded article to the disputes between former Bolshevik leaders, corroborating our assertions about the downfall and morality of the leaders of that revolution.

We regale our readers with a few eloquent excerpts:

"The confrontations in the bosom of the Russian Communist Party usually have a personal and base character. Nevertheless the conflict between the governmental faction led by Stalin and the opposition presided by Trotsky and Zinoviev may exert no small influence on the destinies of the Russian people and therefore deserves the scrutiny of all those interested in intenational politics.

"Present-day Bolshevism is no longer the one that sowed unease in the rest of the world. Its ideas, program and procedures are dfferent. Just as in the beginning the Bolsheviks circulated with enthusiasm the propaganda of world revolution, presently they have no bigger project or object than to keep their hold on power inside the country even at the expense of renouncing the Communist program and of re-establishing the ancien régime...without the Tsar...

"Even the registered legal name of the enterprise has changed. It used to be "Lenin and Trotsky"; today it's "Stalin and Co." What will tomorrow's be?

"The fight between Stalin's men and Trotsky-Zinoviev's is not over ideas or principles: the only goal the combatants have in mind is power. Trotsky, accustomed to the star treatment, balks at becoming a bit player. Trotsky—that "down-and-out Napoleon," as Stalin and his men dub him with acrid irony—supposed that he had the backing of the Army but suffered a bitter disappointment: the Red troops who until recently obeyed Trotsky blindly—just as they would have obeyed any other Red chief or white or even yellow—turned their backs. The "mujik" in soldier's uniform with the Soviet star on his service cap is still too ignorant and averse to all doctrine to form an opinion or bias.

"Zinoviev does not accept his downfall either. Almighty dictator until yesterday, fearsome to 140 million subjects, today he is a politically-defunct nobody. In desperation he calls on those who a short time ago trailed his royal carriage; the Communist Party, the people—but the slaves are already bowing abjectly before their new masters. In vain does Zinoviev also call on the Communist parties abroad whose boss he was for the past eight years: everyone scurries away from the fallen chief.

"The Government of the Kremlin, with the pretext of preserving Party unity, gave strict orders to curb the activity of the rebels. All attempts by Trotsky, Zinoviev and Company to deliver a speech at a factory meeting or somewhere else were futile. The Communists who not too long ago welcomed the appearance of those fallen gods on the rostrum with enthusiasm now shouted at them, "That's enough! Shut up! Get out!" Trotsky was expelled from several garrisons where he wished to speak, as well as from several meetings. As regards Zinoviev he was greeted with whistles [hisses] and insults in Petrograd itself where he had been its captain-general for more than eight years.

"'Sic transit gloria mundi!'

"Despite it all, the opposition does not want to lay down its arms. Trotsky, Zinoviev and their colleagues are perfectly aware that they have lost the battle. But the Rubicon has been crossed and there is no way back."

Let our readers apprehend "Bolshevism's delights" and the "austerity" of its leaders.

D. C.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |