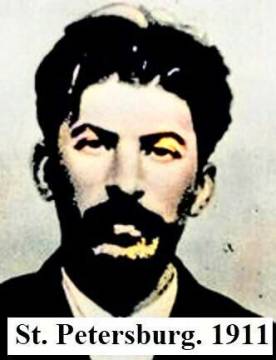

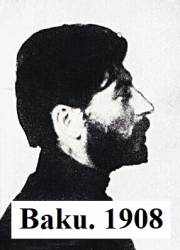

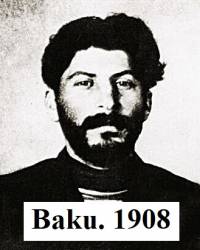

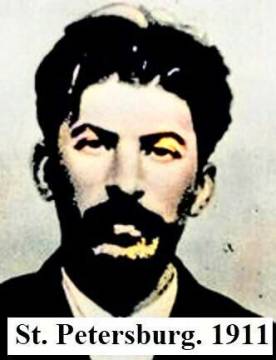

Left: J. V. Stalin in 1911. Right: Monument in Solvychegodsk to Stalin (1953). Nonextant today.

Sources: webpage (left), webpage (right). Both photographs were edited with Lunapic

1. ECONOMIC TERRORISM AND THE LABOUR MOVEMENT.

(Gudok [The Siren], 25. Old Style March 30, 1908)

The workers' struggle does not always and everywhere assume the same form.

There was a time when workers fought their employers by smashing machines and setting fire to factories. At that time the workers said, "Machines are the cause of poverty! The factory is the seat of oppression! Therefore smash and burn them!"

That was the period of disorganized anarchist-rebel conflicts.

We also know of other cases where workers disillusioned with arson and destruction adopted "more violent forms" such as killing directors, managers, foremen, etc. The workers said, "It's impossible to destroy all machines and all factories—and it's not in our interest to do so—but it's always possible to frighten the managers and knock the starch out of them by means of terrorism. Therefore beat them up, scare them!"

This was the period of individual terrorist conflicts stemming from the economic struggle.

The labour movement condemned both forms of struggle sharply and made them a thing of the past.

This is understandable. There is no doubt that the factory is indeed the seat of exploitation of the workers and that the machine still helps the bourgeoisie to aggravate the exploitation, but this does not mean that the machine and the factory are themselves the cause of poverty. On the contrary, precisely the factory and the machine will enable the proletariat to break the chains of slavery, abolish poverty and vanquish all oppression once factories and machines are transformed from private property (of individual capitalists) to public property.

On the other hand, what would our lives be like if we wrecked and burned the machines, factories and railways? Our lives would become a dreary desert and the workers would be the first ones to lose their livelihood!...

Clearly we must not wreck machines and factories but gain possession of them when that becomes possible—if we are indeed striving to end poverty.

That's why the labour movement rejects anarchist-rebel conflicts.

Withal there is no doubt that economic terrorism has some apparent "justification" insofar as it intimidates the bourgeoisie. But what use is this intimidation if it is transient and fleeting? That it can only be transient is clear from the one fact alone that it's impossible to resort to economic terrorism always and everywhere. That's the first point.

The second point is: Of what use is to us the fleeting fear of the bourgeoisie and the concessions it may wring from them if we do not have behind us a powerful mass organization of workers that will always be ready to fight for the workers' demands and be capable of preserving the concessions gained?

Indeed facts convince us that economic terrorism diminishes the desire for such an organization and deters workers from uniting and acting with an independent political voice because they already have terrorist heroes who act on their behalf! 1

Should we cultivate a spirit of independent political action by the workers? Should we cultivate a desire for unity amongst them? Of course we should! But can we resort to economic terrorism if it snuffs out both?

No, comrades! It's against our principles to terrorize the bourgeoisie by means of individual stealthy acts of violence. Let's leave such "deeds" to the notorious terrorist elements.2

We must come out openly against the bourgeoisie, we must keep it in a state of fear all the time, until final victory is achieved! And for this we do not need economic terrorism but a strong mass organization that will be capable of leading workers in the struggle. That's why the labour movement rejects economic terrorism.

In view of the above, the resolution recently adopted by the strikers at Mirzoyev's 3 against arson and "economic" assassination holds special interest.

In this resolution the joint commission of the 1,500 men at Mirzoyev's cites the case of arson in a boiler room of Balakhany and the "economic" murder of a manager in Surakhany and declares that it "protests against such methods of struggle as assassination and arson" (see Gudok, 24).4

By this the men at Mirzoyev's publicized their final rupture with the old terrorist-rebel tendencies.

By this they resolutely chose the path of the true labour movement.

We greet the comrades at Mirzoyev's and call upon all workers to choose the path of the proletarian mass movement as resolutely as the Mirzoyev comrades have done.

2. THE PRESS.

Napertskali is a Georgian-language newspaper published in Tiflis.1 It's new and at the same time a very old paper for it is the continuation of all the Menshevik newspapers published in Tiflis since 1905. Napertskali is edited by an old group of Menshevik opportunists. But that is not the only point, of course. The main point is that the opportunism of this group is something exceptional, something fabulous.

Opportunism means lack of principle, political spinelessness.

We declare that no Menshevik group has displayed such crass spinelessness as that displayed by the Tiflis group. In 1905 it recognized the role of the proletariat as the leader of the revolution. In 1906 it changed its "position" and declared that "it's no use relying on the workers... the initiative can come only from the peasants." In 1907 it changed its "position" again and stated that "the leadership of the revolution must belong to the liberal bourgeoisie," etc., etc.

Withal their lack of principle has never reached so shameless a degree as it does now, in the summer of 1908.

We have in mind Napertskali's appraisal of the murder of that spiritual enslaver of the dispossessed, the so-called Exarch. The story of this murder is well known.2

A certain group killed the Exarch plus a captain of the gendarmerie returning from "the crime scene" and lastly it attacked a procession of hooligans accompanying the Exarch's body.

Obviously this group was neither a gang of hooligans nor a revolutionary cell because no revolutionary cell would commit such an act at the present time when our forces are being mustered, thus jeopardizing the cause of uniting the proletariat [bold font-weight mine, EFC].

Social-Democracy's attitude toward groups of this kind is commonly known. While ascertaining and combating the causes that give rise to such groups, it wages at the same time an ideological and organizational struggle against them, discredits them in the eyes of the proletariat and dissociates the proletariat from them.

But that is not what Napertskali does. Without ascertaining or explaining anything, it belches forth a few banal liberal phrases against terrorism in general and then goes on to advise, and not only advises but orders its readers to report such groups to the police, to betray them to the police! Disgraceful but a fact unfortunately.

Listen to what Napertskali says: "To haul the murderers of the Exarch before a court is the only way to erase this stain forever... Such is the duty of the advanced elements."

Social-Democrats in the role of voluntary police informers—this is what the Menshevik opportunists have brought us to in Tiflis!

The political spinelessness of the opportunists is no mysterious carbuncle. It springs up from an irresistible urge to adapt oneself to the tastes of the bourgeoisie, to please the "masters" and earn their praise. That's the psychology of the opportunist tactics of adaptation. And so, to sit well with the "gentry," please them or at all events avert their wrath over the murder of the Exarch, our Menshevik opportunists grovel like flunkeys before them and take upon themselves the role of police sleuths!

Such adaptation tactics can not be surpassed!

Baku is among the cities in the Caucasus that produce original versions of opportunism.

There is a group in Baku which lies still more to the right and is therefore more unprincipled than the Tiflis group ... We are referring to the Shendrikovite Pravoye Delo group, progenitors of the Baku Mensheviks.3

True, this group has long ceased to exist in Baku; to escape the wrath of Baku workers and their organizations it had to migrate to St. Petersburg.4

But it sends its screeds to Baku, writes only about Baku affairs, seeks supporters precisely in Baku, strives to "win over" the Baku proletariat. It will not be amiss therefore to talk about this group.

We turn over the pages of their newspaper and before our eyes unfolds the old picture of the old shady gang, Messrs. the Shendrikovs.

Here is Ilya Shendrikov the well-known "handshaker" of General Junkovsky, a veteran of backstage intrigue (photograph on the right).5

Here also is Gleb Shendrikov, now in retirement, the former Socialist-Revolutionary, the former Menshevik, the former "Zubatovite."

And here is the celebrated chatterbox, the "immaculate" Klavdia Shendrikova, a pleasant lady in all respects.

Nor is there a dearth of "followers" of various sorts, like the Groshevs and Kalinins, who played a part in the movement sometime ago but who are behind the times now and are living only of their reminiscences.

Even the shade of the late Lev rises before us... In short, the whole picture!

But who needs all this? Why are these inglorious shadows of a gloomy past thrust upon the workers? Are they calling on workers to set fire to the derricks? Or to vilify the Party and trample it in the mire? Or to go to the "no-workers" conference and then strike a shady deal with Mr. Junkovsky?

No! The Shendrikovs want to "save" the Baku workers! They "see" that after 1905, i.e., after the workers had driven them out, "the workers find themselves on the brink of a precipice" and so the Shendrikovs print Pravoye Delo to "save" the workers, to lead them out of the "blind alley." To do this they propose that workers return to the past, forsake the gains of the last three years, turn their backs on Gudok and Promyslovy Vestnik, ditch the existing unions, send Social-Democracy to the devil and, after expelling all non-Shendrikovites from workers' commissions, rally round conciliation boards. Strikes and illegal organizations are no longer necessary. What the workers need is those conciliation boards where the Shendrikovs and the Gukasovs 6 will "settle disputes" with Mr. Junkovsky's leave.

That's how they want to lead the Baku labour movement out of the "blind alley."

[...]

But is not this how the workers were "saved" by Zubatov in Moscow, by Gapon 7 in St. Petersburg and by Shayevich in Odessa? And did they all not turn out to be mortal enemies of the workers?

Whom then do these hypocritical "saviours" want to swindle in broad daylight?

[...]

The Baku proletariat is politically conscious enough to be able to tear your masks off and put you in your proper place!

Who are you? Where do you come from?

You are not Social-Democrats; for you grew up and are living in conflict with Social-Democracy, in conflict with the Party principle! 8

Nor are you trade unionists; for you trample workingman unions in the mire, workingman unions that are naturally suffused with the spirit of Social-Democracy!

You are just Gaponites and Zubatovites hypocritically wearing the mask of "friends of the people"!

You are enemies inside the camp and therefore the most dangerous enemies of the proletariat!

Down with the Shendrikovites! Turn your backs on the Shendrikovites!

That's our answer to your Pravoye Delo, Messrs. the Shendrikovs!

And that's how the Baku proletariat will respond to your hypocritical advances!...

3. THE PARTY CRISIS AND OUR TASKS.

It is no secret to anyone that our Party is passing through a severe crisis. The Party's loss of members, the shrinking and weakness of the organizations, the latter's isolation from one another and the absence of co-ordinated Party work, they all show that the Party is ailing, coursing through a grave crisis. To appreciate at once the full gravity of the crisis it is sufficient to point to St. Petersburg where in 1907 we had about 8,000 Party members and currently we can scarcely muster three-to-four hundred. We shall not discuss Moscow, the Urals, Poland, the Donets Basin, etc., which languish in a similar state.

The first factor particularly depressing the Party is the isolation of Party cells from the broad masses. At one time our cells had thousands in their ranks and they led hundreds of thousands. At that time the Party had firm roots among the masses. This is not the case now. Instead of thousands, tens and hundreds at most stayed put. And as regards leading hundreds of thousands, it's not worth discussing.

True, our Party wields broad ideological influence among the masses; the masses know the Party; the masses respect it. That is primarily what distinguishes the "post-revolution" Party from the "pre-revolution" one; but that's all the Party's influence amounts to in practice.

Ideological influence by itself is far from enough. Breadth of ideological influence is offset by lack of organizational consolidation. That is why our cells are isolated from the broad masses.

But that is not all. The Party is suffering not only from isolation but also from the fact that the Party cells are not linked together, they do not have a common Party life but are divorced one from another. St. Petersburg doesn't know what is going on in the Caucasus, the Caucasus ignores what is happening in the Urals, etc. Each nook has its own separate life.

Strictly speaking, we no longer have one Party with the collective life we all boasted about in the period 1905-1907. We are working in a most scandalous amateurish way. The organs currently published abroad do not and cannot link the cells scattered across Russia, cannot endow them with a collective life. Indeed it would be odd to think that organs published abroad, far removed from the Russian reality, could co-ordinate the work of a Party that has long outstripped its study-circle phase.

True, the isolated cells have much in common ideologically. They share the programme that withstood the test of revolution, they share practical principles validated by the revolution and they have glorious revolutionary traditions in common. Incidentally this is the second important difference between the "post-revolution" Party and the "pre-revolution" one. But it's not enough.

The point is that the ideological unity of Party cells does not by a long shot save the Party from want of organizational cohesion and from its isolation. It suffices to point out that the Party does not even have satisfactory courier service. How much harder then it must be to make the Party a single organism.

Thus: (1) the Party's isolation from the broad masses and (2) disjointed Party cells is the crux of the crisis affecting the Party.

It's not difficult to understand that all this is caused by the crisis in the revolution itself, the interim triumph of the counter-revolution, the lull after the storm and, lastly, the loss of the semi-liberties enjoyed in 1905-1906. The Party flourished, expanded and strengthened as the revolution progressed and liberties existed. Liberties vanished, the revolution retreated and the Party began to ail. Intellectuals deserted it and were followed by the most skeptical workers. In particular the departure of intellectuals accelerated with the ideological maturing of the Party or, rather, of the advanced workers who with their highbrow musings outgrew the meagre stock-in-trade of the "intellectuals of 1905."

It by no means follows from all this, of course, that the Party must vegetate in this state of crisis until future liberties arrive, as some people mistakenly think. In the first place the arrival of fresh liberties depends largely on whether the Party will emerge from the crisis healthy and rejuvenated. Liberties do not drop from the skies. They are won thanks to, among other factors, the existence of a well-organized workers' Party. Secondly, the universally known laws of class struggle tell us that a greater organization of the bourgeoisie must inevitably bring a greater organization of the proletariat. And everybody knows that the renewal of our unique Party is a prerequisite for a greater organization of our proletariat as a class.

Consequently our Party's recovery before fresh liberties arrive is not only possible, it's inevitable.

The whole point is to discover how to bring about that recovery. How can the Party (1) link up with the masses, and (2) fuse its cells into a single body?

[...]

The Party is suffering primarily because it is isolated from the masses; it must join them at all costs.

This is doable primarily and mainly via addressing those issues that currently excite the broad masses. Take, for example, their penury at the hands of Capital. Massive lockouts sweeping over workingmen like a hurricane, production cutbacks, arbitrary dismissals, lower wages, longer working hours and a general capitalist offensive persist to this day. It can hardly be imagined how much suffering all this is causing the workers, how much it's making them ponder, what a host of "misunderstandings" and conflicts erupt between them and their employers, what a raft of interesting questions occupy the minds of workingmen.

Let our Party cells, in addition to their political work, intervene in all these minor conflicts constantly, let them staple these conflicts to the great class struggle and, backing the masses in their daily protests and demands, demonstrate to them the great principles of our Party by way of actual deeds. The task is to make the Party committees of factories and workshops the preeminent bastions of the Party. All that is required is for those committees to intervene in all the affairs of the workers' struggle constantly, to champion their everyday goals and to staple those goals to the historical task of the working class.

[...]

Of still greater importance for overcoming the Party crisis is the composition of Party cells. The most experienced and influential advanced workers must take the lead in every task, they must occupy the top posts—from practical or managing posts to literary positions. Our organizational slogan must be: "Clear the way for advanced workers in all the spheres of Party activity," "Give them broader scope!"

[...]

In short, (1) intensified agitation around the daily needs of workers but heeding the loftier aims of the working class, (2) designation and consolidation of factory and workshop committees as key Party district centres, (3) the "transfer" of top Party posts to advanced workers, and (4) the creation of "discussion groups" for advanced workers to expand their knowledge of the theoretical and practical aspects of Marxism.

[...]

The Baku organization has systematically intervened in all affairs of the workers' struggle and has hardly missed a single conflict between the workers and the oil barons while at the same time, of course, conducting broad political agitation.2

Incidentally this explains why the Baku cell has kept in touch with the masses to this day.

[...]

And so, how can isolated Party cells be linked together, how can they be fused into a single well-knit Party with a collective life?

[...]

Evidently, a radical measure is needed.

The only radical measure possible is the publication of an all-Russian newspaper, a newspaper that will serve as the centre of Party activity and be published in Russia. It will be possible to bond the cells scattered across Russia only on the basis of communal Party activity. But communal Party activity will be impossible until the experience of the local cells is collected at a headquarters which will later display the experiences of the whole Party to every local cell.

An all-Russian newspaper could then guide, co-ordinate and direct Party activity; but in order to do so it must gather from the localities a constant flow of inquiries, statements, letters, information, complaints, protests, plans of work, issues that excite the masses, etc. The newspaper staff will analyze all this data, extract conclusions, directives and slogans and bring them to the knowledge of the entire Party.

If these conditions are not met, no Party leadership is viable, and if there is no leadership the local Party cells cannot coalesce permanently into a single whole! That's why we stress the need for precisely an all-Russian newspaper (not one published abroad) and precisely a leading newspaper (not simply a popular one).

Needless to say, the only institution that can launch and manage such a newspaper is the Party's Central Committee whose duty it is to guide Party work anyway. It is performing this duty poorly and, as a result, the local cells are almost completely divorced from one another.

[...]

Thus the present task is an all-Russian newspaper to be the organ that will coalesce and rally the Party round the Central Committee. This is the way to overcome the crisis currently affecting the Party.

4. RESOLUTION OF THE BAKU COMMITTEE ON THE DISAGREEMENTS IN THE ENLARGED EDITORIAL BOARD OF PROLETARY. 1

The Baku Committee discussed the situation on the enlarged Editorial Board of Proletary 3 on the basis of the printed documents submitted by both sections of the Board, and arrived at the following conclusions.

(1) As far as the substance of the matter is concerned, the stand taken by the majority on the Editorial Board regarding tasks inside and outside the Duma is the only correct one. The Baku Committee believes that only this stand is truly Bolshevik, Bolshevik in spirit and not just in letter.4

(2) "Otzovism" underrates the legal possibilities for political agitation particularly in the Duma. Otzovism is harmful to the Party.5

The Baku Committee asserts that under the present lull, in the absence of better means of conducting open Social-Democratic agitation, using the Duma platform can and should be one of the most important Party tasks.

(3) "Ultimatumism"—constantly reminding the Duma bench about Party discipline—is not a trend in the Bolshevik camp.6

"Ultimatumism" is the worst species of "Otzovism" insofar as it tries to pose as a separate trend which confines itself to demonstrating the rights of the Central Committee over the Duma bench. The Baku Committee asserts that constant work by the Central Committee directed to the Duma deputies and elsewhere can alone make the bench a truly disciplined Party delegation. The Baku Committee believes that the work of the Duma deputies over the past few months clearly proves all this.

(4) So-called "god-building" as a literary trend and in general the introduction of religious elements into socialism is the result of an interpretation of the principles of Marxism that is unscientific and therefore harmful for the proletariat.7

The Baku Committee emphasizes that Marxism took shape and developed into a definite world outlook not as the result of an alliance with religious elements but as the result of an implacable fight against them.

(5) The Baku Committee is of the opinion that an implacable ideological fight against the above-mentioned trends espoused by the minority on the Editorial Board is one of the most urgent and immediate tasks of the Party.8

[...]

5. OUR AIMS.

Anyone who reads Zvezda 3 and knows its columnists, themselves contributors to Pravda, will not find it difficult to understand the line Pravda will pursue.

Pravda aims to illuminate the path of the Russian labour movement with the light of international Social-Democracy, to spread the truth amongst the workers as to who their friends and foes are and to safeguard the interests of the working class.

In pursuing these aims we do not in the least intend to gloss over the disagreements that exist among Social-Democratic workers. More than that: in our opinion a powerful and virile movement is inconceivable without disagreements, for "complete identity of views" can exist only in the graveyard! 4

But that does not mean that points of disagreement outweigh points of agreement. Far from it!

Much as the advanced workers may disagree among themselves, they cannot forget that, irrespective of what group they belong to, all of them are equally exploited, all are equally disenfranchised. Hence Pravda will chiefly call for unity in the proletarian ranks of the class struggle, for unity at all costs. Just as we must be uncompromising toward our enemies, so must we yield to one another.5

War upon the enemies of the labour movement, internal peace and co-operation within it. That's what Pravda will be guided by in its daily work.

[...]

6. MARXISM AND THE NATIONAL QUESTION.1

The period of counter-revolution in Russia brought not only "thunder and lightning" in its train but also disillusionment and lack of faith in the unity of the labour movement. As long as people believed in "a bright future" they fought side by side irrespective of nationality: workingman issues first and foremost! But when doubt crept into people's hearts they began to drift apart and everyone turned away and headed to his own national tent. Every man for himself! The "national question" first and foremost!

At the same time a profound upheaval was taking place in the economic life of the country. The year 1905 had not been in vain: one more blow had been dealt to the survivals of serfdom in the countryside. The series of good harvests that came after the years of famine and the industrial boom which followed bolstered the expansion of capitalism. Class differentiation in the countryside, urban development, the growth of commerce and improved means of transportation all took a big stride forward. This progress was particularly noticeable in the border regions. And this progress could not but hasten the economic consolidation of the nationalities of Russia and rouse them to action...

The "constitutional regime" then in place also helped to vivify the nationalities. The general spread of newspapers and literature, a certain freedom of the press, cultural institutions, more national theatres, and so forth, all helped to strengthen "national sentiments" doubtlessly. The Duma, elections and political parties gave the nationalities a bigger profile and offered them a new and broad arena for activity.

And the mounting wave of militant Russian nationalism together with the repression exercised by the "powers that be" against border regions for their "love of freedom" triggered a wave of non-Russian nationalism which at times took the form of crude chauvinism.

The spread of Zionism 2 among the Jews, Polish chauvinism, Pan-Islamism among the Tatars, nationalism among the Armenians, Georgians and Ukrainians, the widespread swing of the philistine 3 toward anti-Semitism; all these are generally known facts.

The nationalism wave rolled on ever higher, threatening to engulf the mass of workers. And the more the emancipation movement faded, the more universally nationalism flowered.

At this difficult time Social-Democracy had a lofty mission—to resist nationalism and to protect the masses from the general "epidemic"; for Social-Democracy and Social-Democracy alone could do this by countering nationalism with the tried weapon of internationalism, with the unity and indivisibility of the class struggle. And the more powerfully the wave of nationalism roared, the louder had to be the call of Social-Democracy for fraternity and unity among the proletarians of all the nationalities in Russia. Particular steadfastness was demanded of those Social-Democrats who came into direct contact with the nationalist movement on the border regions. But not all Social-Democrats proved equal to the task; and this criticism applies especially to the Social-Democrats of the border regions.

The Bund, which had previously emphasized carrying out Labour's tasks jointly, now began to stress purely nationalist goals. It went as far as declaring "observance of the Sabbath" and "recognition of Yiddish" a fighting issue in its election campaign.4

The Bund was followed by the Caucasus. A faction of Caucasian Social-Democrats which, like all others, had rejected "cultural national autonomy" is now making it an immediate demand.5

Meanwhile the conference of the Liquidators has in a diplomatic way sanctioned nationalist vacillations.6

But from this it follows that the views of Russian Social-Democracy on the national question are not yet clear. Evidently a serious comprehensive discussion of the national question is required. Consistent Social-Democrats must work solidly and indefatigably against the fog of nationalism, no matter what quarter it comes from.

What is a nation?

A nation is primarily a community, a definite community of people.

This community is neither racial nor tribal. The modern Italian nation was formed from Romans, Teutons, Etruscans, Greeks, Arabs, and so forth. The French nation was formed from Gauls, Romans, Britons, Teutons, and so on. The same must be said of the British, the Germans and others who emerged as nations out of diverse races and tribes.

Thus a nation is not a racial or tribal entity but a historically constituted community of people.

On the other hand the great ancient empires of Cyrus and Alexander can not be called nations although they were constituted historically out of different tribes and races. They were not nations but a casual and loose assortment of ethnicities which uncoupled or melded according to the defeats or victories of this or that conqueror.

Thus a nation is not a casual or ephemeral union but a stable community of people. But not every stable community of people constitutes a nation. Austria and Russia are stable communities but nobody calls them nations.

What distinguishes a national community from a state community? Among others, the fact that a national community is inconceivable without a national language whereas a state may have more than one language; we are referring of course to the languages people speak, not to some official language of the state. The Czech nation inside Austria and the Polish nation inside Russia would not exist without their own national language. Withal the integrity of Austria and Russia is unaffected by the existence of several languages within their borders.

Thus a common language is a characteristic of a nation.

This, of course, does not mean that different nations always and everywhere must speak different languages or that all who speak a common language necessarily conform a nation. A national language for every nation, but not necessarily different languages for different nations! Englishmen and Americans speak the same language, yet they do not constitute one nation. The same is true of Norwegians and Danes or of Englishmen and Irish.

But why, for instance, do Englishmen and Americans not constitute a single nation though they speak the same language?

Firstly, because they inhabit different lands. A nation is formed only as a result of prolonged systematic intercourse, as a result of people being together generation after generation. But people cannot live together for extended periods of time unless they inhabit a common territory. Englishmen and Americans originally did in England. Later a fraction of Englishmen sailed to a new land, America, and there, in the course of time, created the American nation. Territorial separation brokered the creation of a new nation.

Thus a common territory is another characteristic of a nation.

But this is not all. A common territory does not by itself make a nation. Nationhood requires a shared economic space to weld the various parts of the country together. There is no such bond between England and America and so they are two different countries, yet the Americans themselves would not deserve to be called a nation if their states were not joined like the spokes of a wheel to a shared economic loop through the division of labour, efficient means of communication, and so forth.

Take the Georgians, for instance. Georgians before the Reform inhabited a common land and spoke one language. Nevertheless they did not, strictly speaking, conform a nation because their independent principalities did not have a common economic life. For centuries they waged war on one another and pillaged each other by forging alliances with the Persians or the Turks. Some casual union of principalities brought about by some king rapidly wilted under the whims of princes and the indifference of the peasants. Georgia became a nation only in the latter half of the nineteenth century when the abolition of serfdom and material progress, modern means of communication and the surge of capitalism, introduced division of labour across the breadth of the land, shattered the economic islets and forced them to have a shared economic life.

The same may be said about all other nations that exited the feudal phase and entered the stage of developed capitalism.

Thus a common economic life, economic cohesion, is another characteristic of a nation.7

But even this is not all. Apart from the preceding, one must take into consideration the spiritual complexion of the people who make up a nation. Nations differ not only in their living conditions but also in their spiritual complexion embedded in a national culture. If England, America and Ireland, which speak the same language, are nevertheless three distinct nations it is due in no small measure to the varying psychological make-up kneaded from generation to generation in response to dissimilar conditions of existence.

Of course psychological make-up or "national character" (as is otherwise called) is intangible to an observer, but insofar as it buds a distinct culture easily identifiable with the nation it becomes tangible and cannot be ignored. Needless to say, "national character" is not set once and for all but is subject to change by changes in the living conditions. Since it is always present it defines the nation's character.

Thus a common psychological make-up manifested as a common culture is another characteristic of a nation.

We have now exhausted the characteristic features of a nation.

A nation is a historically constituted, stable community of people formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture.

It goes without saying that a nation, like every historical phenomenon, is subject to the law of change. Nations have a history, a beginning and an end.

[...]

It might seem that "national character" is not a characteristic but the essence of a nation and that all other characteristics are, properly speaking, simply conditions for the birth and growth of a nation.

Such, for instance, is the view held by R. Springer and especially by O. Bauer. Social-Democrat theoreticians on the national question. Both men are well known in Austria. Let us examine their theory of the nation.

According to Springer,

A nation is a union of similarly thinking and similarly speaking persons ... It is a cultural community of modern people no longer tied to the 'soil' (italics are Stalin's).8

Thus a "union" of similarly thinking and similarly speaking people, no matter how disconnected they may be, no matter where they live, is a nation.

Bauer goes even farther,

What is a nation? Does a common language make people a nation? But the Englishmen and the Irish ... speak the same language without, however, being one people; the Jews have no common language and yet are a nation.9

What then is a nation?

A nation is a relative community of character.10

But what is character, in this case national character?

National character is the sum total of characteristics that distinguish the people of one nationality from the people of another nationality—the composite sum of physical and spiritual characteristics that distinguish one nation from another.11

Bauer knows, of course, that national character does not drop from the skies, so he adds:

The character of a people is determined by nothing so much as by their destiny ... A nation is nothing but a community with a common destiny 12 ... (determined) by the conditions under which people produce their means of subsistence and distribute the products of their labour.13

We thus arrive at the most "complete" (as Bauer labels it) definition of a nation:

A nation is an aggregate of people bound into a community of character by a common destiny.14

We thus have common national character based on a common destiny, but not necessarily connected with a common territory, language or economic life.

But what then remains of the nation? What common nationality can there be among people who are economically disconnected, inhabit different lands and from generation to generation speak different languages?

Bauer speaks of the Jews as a nation although they "have no common language."

But what "common destiny" and national cohesion is there, for instance, between Georgian, Daghestanian, Russian and American Jews who dwell apart, inhabit different lands and speak different languages?

The above-mentioned Jews undoubtedly lead their economic and political life in common with the Georgians, Daghestanians, Russians and Americans respectively, and they live in the same cultural environment as these; and that is bound to influence their national character.

If there is any commonality left to them it is their religion, their common origin and certain relics of the national character. All this is beyond question. But how can it be seriously maintained that petrified religious rites and fading psychological relics affect the "destiny" of these Jews more powerfully than the living social, economic and cultural environment surrounding them?

It is only on this assumption of commonality that it is possible to speak of the Jews as a single nation at all. But what then distinguishes Bauer's nationhood from the mystical and self-sufficient "national spirit" of the spiritualists?

[...]

We said above that Bauer, while granting the necessity of national autonomy for the Czechs, the Poles and so on, rejects a similar autonomy for the Jews. In answer to the question, "Should the working class demand autonomy for the Jews?" Bauer says that "national autonomy cannot be demanded by Jewish workers." According to him, the reason is that "capitalist society makes it impossible for them to continue as a nation."

In brief the Jewish nation is coming to an end and hence there is nobody to demand national autonomy for. The Jews are being assimilated.

This view on the fate of the Jews as a nation is not a new one. It was expressed by Karl Marx as early as the eighteen forties in reference chiefly to German Jews.15

It was repeated by Kautsky in 1903 in reference to Russian Jews.16

It is now being repeated by Bauer in reference to Austrian Jews with the caveat that he denies not the present but the future of the Jewish nation.

Bauer explains the impossibility of preserving the existence of the Jews as a nation by the fact that "the Jews have no closed territory of settlement."

This explanation, in the main correct, does not express the whole truth however. The fact of the matter primarily is that among Jews there is no large and stable stratum connected with a land that would naturally rivet the nation together, serving not only as its armature but also as a "national" market. Out of the five or six million Russian Jews only 3-4% are tied to agriculture in some manner. The remaining 96% work in commerce, industry or in urban institutions scattered across Russia. Moreover they are in general town dwellers and do not constitute a majority in a single gubernia.17

Thus interspersed as national minorities in areas inhabited by others, the Jews as a rule serve "foreign" nations as manufacturers and traders or as liberal professionals, naturally adapting themselves to the "foreign nations" in respect of language and so forth. All this taken together with the enhanced shuffling of nationalities characteristic of developed capitalism leads to the assimilation of the Jews. The abolition of the "Pale of Settlement" would only serve to hasten this process of assimilation.

Consequently the question of national autonomy for Russian Jews assumes a somewhat curious character: autonomy is being proposed for a nation whose future is denied and whose existence still has to be proven!

[...]

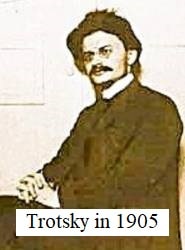

7. STALIN'S EARLY SPLEEN TOWARD TROTSKY.

1. The London Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party, p. 52. Year 1907.

As regards the different trends revealed at the congress it must be noted that the formal division into five groups (Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Poles, etc.1) retained a certain validity, albeit inconsiderable, only up to the discussion on questions of principle (the question of the non-proletarian parties, the labour congress, etc.). When these questions of principle came up for discussion the formal division in fact disappeared, and when a vote was taken, the congress divided as a rule into two camps: Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. There was no so-called centre or "marsh" at the congress. Trotsky proved to be "pretty but useless."

2. A Letter to the Central Committee of the Party from exile in Solvychegodsk, pp. 215-16. Beginning of 1911.

The plan for a [Lenin-Plekhanov] bloc reveals the hand of Lenin, he is a shrewd fellow who knows a thing or two. But this does not mean that any kind of bloc is good. A Trotsky bloc (he would have called it, "synthesis") would be rank unprincipledness, a Manilov 2 amalgam of heterogeneous principles, the helpless longing of an unprincipled person for a "good" principle.

3. The results of the elections in the Workers' Curia of St. Petersburg, pp. 265-67. Year 1912.

Trotsky recently wrote in Luch 3 that Pravda was once for unity, but is now against it.

Is that true? It's true and yet not true. It's true that Pravda was for unity. It's not true that it is now against unity: Pravda always calls for the unity of consistent workers' democracy.

What is the point then? The point is that Pravda and Luch and Trotsky look at unity in totally different ways. Evidently there are different types of unity.

Pravda is of the opinion that only Bolsheviks and pro-Party Mensheviks can be united into one body. Unity on the basis of dissociation from anti-Party elements, from Liquidators! Pravda has always stood and always will stand for that kind of unity.

Trotsky, however, looks at the matter differently: he jumbles everybody together, opponents of the Party principle as well as supporters.

And of course he gets no unity whatever: for five years he has been conducting this childish propaganda in favour of uniting what cannot be united, and what he has achieved is that we have two newspapers, two platforms, two conferences and not a scrap of unity between workers' democracy and the Liquidators!

And while the Bolsheviks and pro-Party Mensheviks are gelling more and more into one unit, the Liquidators are digging a chasm between themselves and that unit.

The practical experience of the movement confirms Pravda's scheme of unity and smashes Trotsky's childish plan of uniting the ununitable.

More than that. From an advocate of a fantastic unity Trotsky is turning into an agent of the Liquidators, doing what suits the Liquidators.

Trotsky has done all in his power to ensure that we should have two rival newspapers, two rival platforms, two conferences that repudiate each other. And now this champion with fake muscles is singing us a song about unity!

This is not unity, it's an antic worthy of a comedian.

4. The elections in St. Petersburg, p. 288. Year 1913.

It is said that by his "unity" campaign Trotsky introduced a "new current" into the Liquidators' old "affairs." But that is not true. In spite of Trotsky's "heroic" efforts and "terrible threats" he, in the end, has proven to be merely a vociferous champion with fake muscles, for after five years of "work" he has succeeded in uniting nobody but the Liquidators.

New noise, old deeds!

Summing up, Stalin portrays Trotsky as a "pretty but useless" centrist, unprincipled, a fop who attempts to unite what can not be united, someone on the verge of becoming an anti-Party figure, a flabby champion and a blustering comedian.

Stalin held to this opinion all life long.

At the start of the Russian Civil War he again slighted Trotsky, in a letter to Lenin,

For the good of the work I need military powers. I have already written about this but got no reply. Very well, in that case I shall myself without any formalities dismiss Army commanders and commissars who are ruining the work. The interests of the work dictate this and of course not having a paper from Trotsky is not going to deter me.

(Letter to V. I. Lenin. July 10, 1918, Tsaritsyn. Collected Works of J. V. Stalin, 4, p. 123)

Stalin's judgement was not too far off the mark for after Lenin's death it barely took him a year to depose Trotsky from the post of Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council.

8. BAKU, TIFLIS, VOLOGDA.

Tiflis: An individual threw a dynamite bomb at Police. Two policemen were killed and two passersby injured.

Baku (Madrid 3, 8:40 PM): Naphtha factory workers have gone on strike.

Baku (Madrid 25, 10:00 AM): On crossing a section of railway switches a train fortuitously killed a worker. Fellow workers opened fire on the train. The engineer pushed the throttle full steam ahead, crushing ten workers and injuring several. Troops had to intervene to restore order.

Tiflis: Police detained an individual with an awful criminal record on suspicion of being linked to a bomb explosion at one of the schools in this city.

Tiflis (Madrid 25, 10:00 PM): Reports from St. Petersburg say that peasants in a hamlet near Tiflis refused to hand over two revolutionaries to the authorities. The Cossacks charged them, killing twelve. The peasants fired back with revolvers, killing two Cossacks and seriously wounding a third.

Baku: Ten terrorists were arrested in Baku for being the authors of a house explosion which killed several policemen. These had been lured to the house by the revolutionaries.

Tiflis (Madrid 6, 10:00 AM): A mail courier escorted by four Cossacks was surprised by bandits near Tiflis. The bandits hurled three bombs at the convoy and opened rifle fire. A Post Office employee was killed, another seriously wounded. The assailants made away with twenty thousand rubles. The Cossacks killed a bandit and captured another.

Baku (Madrid 23): Russian newspapers deal at length with a police scandal whose first fallout has been the destitution of the head of the St. Petersburg secret police. It's a knotty story. This is what happened:

For some time now Baku terrorists had not shown any signs of life.1 The population, so cruelly chastised by the revolutionaries and by the police, was starting to recover from past horrors when several bombs exploded downtown in less than a week, causing some vicims. The authorities stated that the new cases were the work of a secret anarchist organization and proceeded to arrest several individuals.

Since bombs kept exploding, the municipal police began to make searches. One search uncovered a cache of dynamite bombs in a house; the landlord was arrested.

No one knew the landlord in Baku. He turned out to be a secret police agent from St. Petersburg. Under pressure from high quarters the man was provisionally released; but St. Petersburg newspapers got wind of the affair and raised a hullabaloo that compelled Baku Police to put him in jail once more.

The man made convincing declarations that the secret police has been planting bombs in various capitals to obtain rewards and to justify the massive jailings, deportations and internal exiles.

Several underlings and agents have been imprisoned and destituted since. The entire liberal press has mounted a vigorous campaign for the dissolution or reform of the sinister secret police.

Vologda (Spain's General Inspection of International Health): According to official news relayed to this Centre by the Consul of our Nation in St. Petersburg there have been cases of cholera recorded in the gubernias of Vologda,1 Pskov, Smolensk, Volhynia, Orel, Tver, Yaroslavl, Perm, Vyatka, Orenburg, Kutais, Erivan, Tomsk, Tobolsk. Let this be known to the business community in general and to port and frontier health authorities (Madrid. September 28, 1910).

Vologda: A dramatic scene unfolded in Vologda's theater hall, according to reports from St. Petersburg.

Some time ago a Vologda young man was jailed, convicted of fellow-traveling with a revolutionary outfit. His lover, a very beautiful young woman, went to see him whenever prison regulations allowed.

In one of those visits the young man bleated about being treated with the utmost harshness and that he had been given several whiplashes for having complained about the poor quality of the food.

The young woman, rightly indignant, ran to the home of Vologda's inspector of prisons, Alexander Efimov.

The inspector hosted her with very little courtesy, heard her complaint coldly and answered, "Leave and don't get involved in what is none of your business. Prison inmates are treated as they deserve. If you insist on denouncing alleged abuses, they will imprison you too." The young woman wept and pleaded in vain. Efimov refused to hear her out.

The days passed and she went to visit her lover once more. She found him pallid, scrawny, his eyes glistening from the fever. "I am going to die irremediably here," he said to her, "Efimov came the other day to the prison and spoke to the director about you. Since then my harsh treatment has worsened." She listened in silence, bid him farewell and departed glum.

The day before yesterday Efimov went to the theater with his wife. The couple took fourth-row seats. Behind them sat a woman dressed in black, the young man's lover, her hands tucked in a muff.

In one of the play's climactic scenes, when the eyes of the audience were riveted on the stage, the young woman stood up, slung the muff off to the aisle and screamed, "Efimov! Turn around!"

The inspector did so, surprised, and his eyes fastened on the young woman pointing a gun straight at him.

"Don't shoot, please!" he said, rising. She opened fire. The first bullet hit Efimov's right hand. The second one entered the nape as he wheeled to the front; he shrieked and fell face first over the patrons seated in the third row.

His wife attempted to grab the female gunner on her own, but she fired almost point-blank a bullet that struck her full in the face.

Her vengeance fulfilled, the female terrorist stepped out onto the aisle. Some patrons tried to seize her. She pointed the gun at them and shouted, "I have three bullets left! Who wants them?" And as she saw all staying back she shouted, "I have killed a wretch! Get out of my way!"

She raced to the lobby and disappeared in the night.1

It's supposed that she is hiding in a house on Vologda's outskirts.

Stalin left Volodga without authorization on February 29 (March 13), 1912, and spent a month in Baku and Tiflis, directing the work of the Transcaucasian Bolshevik Committees. In April he moved secretly to St. Petersburg and was arrested almost upon arrival. In July he was deported to the Narym Territory.

Stalin escaped from the Narym Territory and returned to St. Petersburg on September 12 (25), 1912. There he edited Pravda, wrote articles and travelled to Moscow and to Krakow (Poland).

St. Petersburg: An automobile carrying 10,000 cartridges of dynamite exploded. The car was demolished and the chauffeur "totally crippled".

St. Petersburg (Madrid 8, 10:20 PM): The general elections across the empire are over. The Rights have obtained 260 out of 446 seats.

St. Petersburg (Madrid 24): A new attempt has been made on the life of the Czar of Russia. The intention was to derail the Imperial train. Apprised in time, the train was able to stop and avert the planned regicide.

St. Petersburg (Madrid 28, 10:00 AM): The talks between the Czar of Russia and the Austrian Ambassador were satisfactory and left no doubt about Russia's peaceful intentions.

St. Petersburg: The local Gazeta publishes an interview with a member of the Government who maintains that the new Duma would have to be dissolved if the Octobrists attempt to arrange a bloc with the Leftist minority, for this would create an anti-governmental majority that would significantly endanger the stability of the Duma.

The Russians propose peace. [...] During the night of last Tuesday the Council of People's Commissars sent via radiotelegraph a message to Dukhonin the Chief of Staff ordering him to offer immediately and formally an armistice to all Allied and enemy nations at war.

This message was received at Headquarters yesterday at 5:05 AM ... Simultaneously the same formal armistice proposal was made to all the representatives of the Allies stationed in Petrograd.

Since Dukhonin had not replied by yesterday afternoon, the Council authorized Lenin, Stalin and Krylenko to ask via radiotelegraph the reason for his delay...

| And Now For Something Completely Different |