1. THE RUSSIAN SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC LABOUR PARTY AND ITS IMMEDIATE TASKS.

(Brdzola [The Struggle], 2-3, November-December 1901. Translated from the Georgian language)

Human thought was obliged to undergo considerable trial, suffering and change before it reached scientifically elaborated and substantiated socialism.1

West-European Socialists were obliged to wander blindly in the wilderness of utopian (impossible, impracticable) socialism for a long time before they hewed a path for themselves, investigated and established the laws of social life and thence mankind's need for socialism. Since the beginning of the nineteenth century Europe has produced numerous brave, self-sacrificing and honest scientific workers who tried to explain and answer the question of what can rid mankind of the ills that are becoming more intense and acute with the expansion of trade and industry. Many storms, many torrents of blood swept over Western Europe in the fight to end the oppression of the majority by a minority, but sorrow remained undispelled, wounds stayed open and pain became more and more unbearable with each passing day.

We must regard the fact that Utopian Socialism did not research the laws of social life as a principal reason for this. Utopian Socialism soared higher and higher above life when instead a firm grasp of reality was called for. Utopians sought to create socialism immediately at a time when the ground for it was barren. And what was more deplorable, utopians fancied that socialism could come from the powerful of this world after they were shown the credibility of the socialist ideal (Robert Owen, Louis Blanc, Fourier and others). This outlook hid the labour movement and the working masses from view when these are in fact the sole material vehicle for the socialist ideal.

The utopians could not understand this. They wanted to bring about happiness on earth by legislation, by declarations, without the help of the workers. They paid no attention to the labour movement and often denied its significance. Consequently their theories did not reach the working masses.

The working masses absorbed instead the great idea proclaimed by that genius Karl Marx in the middle of the nineteenth century: "The emancipation of the working class must be the act of the working class itself... Workingmen of all countries, unite!" These words brought out the truth, evident even to the "blind" now, that what can beget the socialist ideal is the independent will and organization of the workers, irrespective of nationality or country.

It was necessary to establish this truth—magnificently done by Marx and his friend Engels—in order to lay a firm foundation for the mighty Social Democratic Party that today hovers like inexorable Fate over European bourgeois society, threatening its destruction and replacement by a socialist society.

The evolution of the idea of socialism followed almost the same path in Russia as it did in Western Europe. Russian Socialists too were obliged to wander blindly for a long time before they reached Social Democratic consciousnes, scientific socialism. Here too there were Socialists and there was a labour movement, but they marched separately: the Socialists headed toward utopian dreams (Zemlya i Volya, Narodnaya Volya) and the labour movement toward spontaneous revolts. Both operated in the same period (1870's-1880's) unaware of each other. The Socialists had no roots in the working class, so their actions were abstract, futile. The workers lacked leaders, organizers, and so their movement took the form of disorderly revolts. This was the main reason why the heroic fight waged by Socialists remained fruitless as their legendary courage was spent against the solid wall of the autocracy.

Russian Socialists contacted the working masses only at the start of the 1890's. They realized that salvation lay only in that class: it alone could bring about the socialist ideal. Russian Social Democracy now concentrated all its efforts and attention on Russian workers. It set to mold this unconscious, spontaneous and raw movement. It attemped to sow class consciousness among the workers, to fuse isolated, sporadic conflicts into a common fight of the oppressed class against the oppressing class; it tried to organize them.

The study-circle phase ended soon. Spurred by external conditions, Social Democracy felt the urge to leave the narrow bounds of the circles behind. The spontaneous movement of the workers had climbed to an exceptional height. Who among you does not remember the year when nearly the whole of Tiflis joined this spontaneous movement? Unorganized strikes at tobacco factories and railway workshops followed one another. Here that happened in 1897-98, in Russia a bit earlier.

Timely assistance was needed and Social Democracy rushed to render it. A struggle started for a shorter workday, the abolition of fines, higher wages and so forth. Social Democracy knew full well that the labour movement should not limit itself to these petty demands; they were not the goal, just a means to it.

Although the demands were petty and the workers fought separately in towns and districts, the struggle itself would teach workers that full victory required the entire working class to join in. It would also show them that beside their first enemy—a capitalist employer—stood another: the organized bourgeoisie, the capitalist state, its Armed Forces, its courts, police, prisons and gendarmerie.

If the slightest attempt of Western European workers to improve their lot clashes with the bourgeois power, if even there—where human rights are law—workers are obliged to confront the authorities, how much more must Russian workers inevitably clash with the autocracy, vigilant foe of every labour movement? The autocracy protects the capitalists and restrains all social classes, especially the most oppressed and downtrodden one: the working class.

That's how Russian Social Democracy perceived the future, so it devoted all its efforts to spread these ideas among the workers. Therein lay its strength, its great and triumphant surge from the very outset, evinced by the great strike of the St. Petersburg weaving mills in 1896 [under the guidance of V. I. Lenin].

But the initial victories misled and turned the heads of certain weaklings. Just as Utopian Socialists had focused their attention exclusively on the ultimate goal and, dazzled, did not see or disowned the growing labour movement, so did certain Russian Social Democrats devote themselves exclusively to the spontaneous labour movement.

At that time (five years ago) [i.e., in the year 1896] the class consciousness of Russian workers was extremely low, they were just then waking up from an age-long torpor. Their eyes, accustomed to the darkness, did not discern clearly the world unveiled to them for the first time. Their needs and demands were not big. Russian workers wanted a slight increase in wages or shorter working hours. The mass of Russian workers had no inkling of the need to change the system, abolish private property, set up a socialist society. They did not envisage abolishing the slavery of the entire Russian people under the autocracy, bringing freedom to the people or taking part in the governance of the country.

And so while a portion of Russian Social Democracy lent its socialist ideas to the labour movement, the other, absorbed in the economic fight, forsook its great duty and ideals completely. Echoing their like-minded friends of Western Europe (called Bernsteinians) they said, "For us the daily strife is everything; the final goal nothing." They were not in the least interested in what the working class was supposed to be fighting for as long as it fought. The so-called farthing policy took hold. Matters reached such an impasse that one fine day Rabochaya Mysl the St. Petersburg newspaper stated, "Our political programme is a ten-hour workday and the restitution of the holidays abolished by the law of June 2, 1897." 2,3

Instead of leading the spontaneous movement, of imbuing the masses with Social Democratic ideals and guiding them toward our final aim, this section of Russian Social Democrats became a blind tool of the spontaneous movement. It followed blindly [khvosted] in the wake of poorly educated workers and confined itself to formulating their conscious needs and requirements. It stood and knocked at an open door, not daring to enter. It did not explain to the working masses the final aim (socialism) or the immediate one (the overthrow of the autocracy). And what was more deplorable still, it deemed both useless and even harmful. It treated Russian workers like children, it was afraid to frighten them with daring ideas. Nor is this all. In the opinion of a certain Social Democracy group it was not at all necessary to wage a revolutionary fight to attain socialism. All that was needed was the economic struggle: strikes, trade unions, co-operative societies of consumers and producers. There you have socialism.

It jettisoned the doctrine of the old [First] International which stated that a change in the existing system or the complete emancipation of the working class was impossible until political power passed to the proletariat (the dictatorship of the proletariat). In its opinion there was nothing new in socialism and strictly speaking did not differ much from capitalist society but could easily fit in. Every trade union, every co-op store or producers' co-op was already a "bit of socialism," they said. They imagined that they could weave new garments for suffering mankind by means of this absurd patching of old clothes! But most deplorable of all and unintelligible to revolutionaries is their extension of the doctrine of their West-European counterparts (Bernstein and Co.) for they state brazenly that political freedom (the freedom to strike, the freedom of association, the freedom of speech, etc.) is compatible with tsarism, that a political struggle to overthrow the autocracy is quite superfluous. If you please, the economic fight alone is the goal. It suffices to have strikes happen more often. The government will tire of punishing the strikers and thus the right to strike and hold meetings will come of its own accord.

Thus these alleged "Social Democrats" argued that Russian workers should devote all their strength and energy to the economic struggle and refrain from pursuing "lofty ideals." Their pragmatic duty was to act in this or that town. They had no interest in the creation of a Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party.4 On the contrary they viewed the prospect as a silly amusing game which would only detract from the "duty" of waging the economic fight. Strikes and more strikes plus the collection of kopeks for strike funds was the alpha and omega of their activity.

You will no doubt suppose that since they had whittled their tasks so much, since they had renounced Social Democracy, these worshippers of the spontaneous "movement" would at least have done a great deal for it. But here too we are disappointed. The evolution of the St. Petersburg movement convinces us of this. The splendid growth and bold progress of the early stages (1895-97) was followed by blind wandering. Finally the movement fizzled out altogether. This is not so surprising because all the attempts of the "Economists" to wage a routine economic fight invariably hit the solid wall of the tsarist government and were shattered. The frightful regime of police persecution curtailed the creation of unions. Nor did strikes bear fruit because 99% were strangled in the clutches of the police. Workers were evicted from St. Petersburg ruthlessly and their revolutionary energy was sapped pitilessly by prison walls and Siberian frosts.

We are deeply convinced that the relative paralysis of the movement was caused by external conditions—the police regime—but no less by the waning of the workers' revolutionary zeal due to a stunted class consciousness. Although the spontaneous movement was growing, most workers did not understand the lofty aims or the context of the struggle because their banner was still the old faded rag with the farthing motto of the economic fight. Hence the workers were bound to fight with less energy, less enthusiasm, less drive. Only a great goal fuels great zeal.

The danger to the labour movement would have been greater had not our standard of living forced Russian workers day after day to direct political strife. Even a minor strike brought workers into conflict with the government and its Armed Forces and glaringly demonstrated the inadequacy of the economic fight. Consequently, despite the wishes of these "Social Democrats," the struggle became increasingly political.

Every attempt of enlightened workers to vent their discontent, every attempt to lift the yoke, led them to stage political demonstrations more frequently. The First of May celebrations opened the door. A new powerful weapon (the political demonstration) was born and it was first flaunted in the great May Day rally of 1900 in Kharkov.

In short, the Russian labour movement transitioned from the sharing of propaganda in study circles and from isolated economic strikes to political struggle and agitation. The shift accelerated as the working class saw others stride resolutely to gain political freedom.5

[...]

2. THE PROLETARIAN CLASS AND THE PROLETARIAN PARTY.

[...]

Up till now our Party has resembled a hospitable patriarchal family, ready to take in all who sympathize. But now that our Party has become a centralized organization it has cast off its patriarchal nature and has become in all respects a fortress whose gates open only to those who are worthy. And that's of great importance to us. At a time when the autocracy is trying to corrupt the class consciousness of the proletariat with "trade unionism," nationalism, clericalism and the like, and when, on the other hand, the liberal intelligentsia is persistently striving to tutor the political independence of the proletariat—at such a time we must be extremely vigilant and never forget that our Party is a fortress, the gates of which are opened only to those who have been tested.

We have ascertained two essential conditions for Party membership (acceptance of the programme and work in a Party organization). If to these we add a third condition, namely, that a Party member must render financial support to the Party, then we shall have enumerated all the conditions that entitle someone to be a Party member.

Hence a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party is someone who accepts the programme of this Party, renders financial assistance to the Party and works in a Party organization.

That is how Paragraph One of the Party Rules drafted by Comrade Lenin was formulated.1

The formula, as you see, springs entirely from the view that our Party is a centralized organization, not a conglomeration of individuals.

Therein lies the supreme merit of this formula.

But apparently some comrades reject Lenin's formula on the grounds that it is "too narrow" and "inconvenient"; they propose another one, presumably not as narrow or inconvenient. We are referring to Martov's formula which we shall analyze now.2

Martov's formula is: "A member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party is someone who accepts its programme, supports the Party financially and renders it regular personal assistance under the aegis of a Party organization."

As you see, this formula omits the third essential condition for membership, namely, the duty of Party members to work inside a Party organization. It appears that Martov regards this definite and essential condition as superfluous and replaces it with the nebulous and indefinite clause, "personal assistance under the aegis of a Party organization." It would appear that someone could still be a member of the Party without belonging to a Party organization (a fine "Party" indeed!) and without feeling obliged to submit to the Party's will (fine "Party discipline" indeed!).

Withal how can the Party "regularly" control individuals who do not belong to a Party organization and thus do not feel absolutely obliged to submit to Party discipline? 3

[...]

3. WORKERS OF THE CAUCASUS, IT IS TIME TO TAKE REVENGE!

[...]

It is time to take revenge!

It is time to avenge our valiant comrades brutally murdered by the tsar's bashi-bazouks in Yaroslavl, Dombrowa, Riga, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Batum, Tiflis, Zlatoust, Tikhoretskaya, Mikhailovo, Kishinev, Gomel, Yakutsk, Guria, Baku and other places!

It is time to call the government to book for the tens of thousands of innocent and unfortunate men who have perished on the battlefields of the Far East. It is time to dry the tears of their wives and children!

It is time to call the government to book for the suffering and humiliation, for the shameful chains it has kept us in for so long! It is time to put an end to the tsarist government and to clear a road for ourselves to the socialist system! It is time to destroy the tsarist government! And we will destroy it.

[...]

Our vital duty is to be ready for that moment. Let us prepare then, comrades! Let us sow the good seed among the broad masses of the proletariat. Let us stretch our hands out to one another and rally around the Party Committees!

We must not forget for a moment that only the Party Committees can lead us worthily, only they will illuminate our path to the "promised land" which is the socialist world!

The party that opened our eyes, identified our enemies, molded us into a formidable army, spurred us to fight our foes, stood by us in joy and sorrow and has always marched out ahead of us—that party is the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party! It and it alone shall lead us in future!

What we must fight for now is a Constituent Assembly elected on the basis of universal, equal, direct and secret suffrage!

Only such an Assembly will give us the democratic republic we need so urgently in our struggle for socialism.

Forward then, comrades! The tsarist autocracy is tottering, our duty is to prepare the decisive assault! It is time to take revenge!

Down With the Tsarist Autocracy!

Long Live the Popular Constituent Assembly!

Long Live the Democratic Republic!

Long Live the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party!

(Reproduced from the manifesto printed on January 8, 1905, at the underground printing press of the Caucasian Union of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party)

4. ANARCHISM OR SOCIALISM?

[...]

Everything in the world is in motion...

Life changes, productive forces grow,

old relations collapse.

Karl Marx

Marxism is not only the theory of socialism but an integral world outlook, a philosophical system from which Marx’s proletarian socialism follows logically. This philosophical system is called dialectical materialism.

Hence to expound Marxism means to expound dialectical materialism.

Why is this system called dialectical materialism?

Because its method is dialectical and its theory materialist.

What is the dialectical method?

It is said that social life is in continual motion and development. And that is true: life must not be viewed as immutable or motionless; it never stalls on a given epoch but is immersed in an eternal process of destruction and creation. Consequently life always harbours the new and the old, the emergent and the decadent, the revolutionary and the counter-revolutionary.

What is born to life and grows day by day is invincible, its progress cannot be checked. If the proletariat, for example, is born to life as a class and grows day by day, no matter how weak and numerically small it may be today it must triumph in the long run. Why? Because it is emerging, growing and striding forward.

On the other hand, what is growing old and lurching to its grave must inevitably court defeat even if it boasts a titanic strength today. If the bourgeoisie, for example, is losing ground gradually, receding more and more each day, then, no matter how strong and numerically big it may be today it must suffer defeat in the long run. Why? Because it is decaying, growing old and feeble, becoming a burden to life.

Hence there arose the well-known dialectical proposition: all that exists and grows day by day is justified by life and all that decays day by day is no longer justified and therefore cannot obviate extinction.

[...]

The consciousness of men does not determine their being,

rather their social being determines their consciousness.

Karl Marx

We already know what the dialectical method is.

What is the materialist theory?

Everything in the world changes, everything in life mutates, but how do these changes happen and in what sequence?

We know, for example, that Earth was once an incandescent fiery mass. Then it cooled progressively. Plants and animals appeared. The development of the animal kingdom brought the appearance of a certain species of ape which gave rise to the appearance of man.

This is how nature developed, broadly speaking.

We also know that social life did not remain stagnant either. There was an epoch when men lived on a primitive-communist basis; at that time they earned their livelihood through primitive hunting, they roamed the forests and procured food. Eventually there arrived another epoch where a matriarchate superseded primitive communism and men satisfied their needs mainly by practising primitive agriculture. Later a patriarchate superseded the matriarchate and men earned their livelihood mainly by breeding cattle. Later a slave-owning system superseded the patriarchate and at that time men earned their livelihood with substantially improved agriculture. The slave-owning system was followed by feudalism and then, after all this, came the bourgeois system.

That is how social life developed, broadly speaking.

Yes, all this is well known... But how did this social evolvement come about; did consciousness call forth the evolvement of "nature" and "society" or did the evolvement of "nature" and "society" call forth the evolvement of consciousness?

This is how materialism approaches the question.

Some people say that "nature" and "social life" were preceded by an Universal Idea which guided evolvement, so that the phenomena of "nature" or "social life" are, so to speak, the rind or crust of the Universal Idea.

Such, for example, was the doctrine of the idealists who in the course of time split into several trends.

Others say that there existed from the very beginning two mutually excluding forces in the world: idea and matter, consciousness and being, and that all phenomena belong to one of these two categories, the ideal and the material, which contend with one another. The evolvement of nature and society then is a continual struggle between ideal and material phenomena.

Such, for example, was the doctrine of the dualists who in the course of time split into several trends like the idealists.

Materialism rejects dualism and idealism outright.

Of course both ideal and material phenomena exist in the world, but this does not mean that they exclude one another. On the contrary, ideal and material phenomena represent two sides of one same nature or society; they cannot be torn apart. They exist and evolve together, so we have no grounds whatever for supposing that they exclude each other.

Thus so-called dualism is unsound.

One single and indivisible nature manifests itself with two different aspects, the material and the ideal. One single and indivisible social life harbors two different qualities, the material and the ideal. That is how materialism perceives the evolvement of nature and of social life, and this perception is called "monism" (oneness).

Materialism repudiates idealism also.

It is wrong to think that an ideal quality or that consciousness in general precedes the evolvement of the physical frame. Nature existed long before living beings. The first living matter had no consciousness, it possessed only irritability and the primeval rudiments of sensation. Later, animals accrued more sensation piecemeal and this evolved slowly into the acquisition of consciousness contingent on their anatomy and the sophistication of their nervous system.

If the ape had always walked on all fours, if it had never stood upright, its descendant—man—would move about likewise and so find it hard to articulate speech, to the crucial detriment of his consciousness. Furthermore had the ape not crouched, its descendant—man—would not walk erect; his brain would log a quadruped's impressions, and this would stymie the development of his consciousness fundamentally.

Therefore it follows that the growth of consciousness requires a certain anatomy and a certain complexity of the nervous system.

Thus it follows that the alteration of an ideal quality (e.g., the onset of consciousness) is preceded by a change in the physical frame plus a favourable set of external conditions: first the external conditions change, i.e., the physical component changes, and then consciousness, the ideal portion, changes alongside.

Thus the history of natural evolution refutes so-called idealism utterly.

The same thing must be said about the history of human society.

History shows that if men were imbued with different ideas and desires in different epochs it was because the men of each epoch confronted nature differently in order to satisfy their vital needs. Accordingly economic relationships assumed different forms. In prehistoric times men tackled nature collectively on the basis of primitive communism, property was communal and therefore men hardly distinguished between "mine" and "thine"; their consciousness was communal. There arrived another epoch where the stance of "mine" and "thine" seeped into the process of production. Property assumed a personal bias and the consciousness of men absorbed the concept of private property. Then came our present era when production is once more a collective undertaking and consequently property will soon assume a collective bias once more; and this is precisely why the consciousness of men is gradually veering toward socialism.

Here is a simple illustration. Let us take a shoemaker who owned a tiny workshop but who, unable to fend off competition from the big manufacturers, closed his workshop and took a job, say, at Adelkhanov's Shoe Factory in Tiflis.1 He went to work at Adelkhanov's not with a view to becoming a permanent wage-earner but with the idea of saving some money, accumulating enough capital to reopen his workshop. As you see, the reality of this shoemaker is already proletarian but his consciousness is still petty-bourgeois through and through. In other words although this shoemaker has lost his petty-bourgeois status his petty-bourgeois consciousness has not yet vanished, it lags behind his present reality.

Clearly the social conditions of men are altered first and then their consciousness shifts accordingly.

But let us return to our shoemaker. As we already know, he intends to save some money and reopen his workshop. This proletarianized shoemaker goes on working but finds that it's very difficult to save money because his salary barely sustains him. Moreover he realizes that opening a private workshop is not so alluring after all: the rent he has to pay for the premises, the customers' whims, the shortage of money, the competition with big manufacturers and similar headaches—such are the many woes that plague a workshop owner. On the other hand the proletarian is relatively carefree; he is not bothered by customers or by having to pay rent for the premises where he works. He goes to the factory in the morning, returns "cheerily" home in the evening and just as cheerily pockets his "pay" every Saturday. Here for the first time the wings of our shoemaker's petty-bourgeois dreams are clipped; here for the first time proletarian notions stir his soul.

Time passes and our shoemaker sees that he does not make enough money to satisfy his most essential needs, that what he needs very badly is a rise in wages. At the same time he hears his fellow-workers talk about unions and strikes. Here our shoemaker realizes that in order to improve his condition he must fight the masters, not reopen his workshop. He joins the union, enters the strike movement and soon becomes imbued with socialist ideas.

Thus the shoemaker's altered social standing prompted a change in his consciousness eventually. First his social standing changed, later his consciousness changed accordingly.

The same must be said about social classes and about society as a whole.

In social life too the external conditions (the material portion) change first. Later men's ideas, habits, customs and world outlook follow suit.

[...]

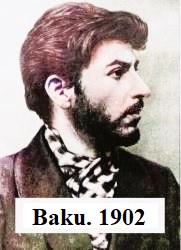

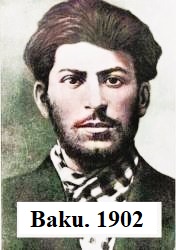

The following information comes from LiveJournal's child webpage entitled, "Return... Leather Production. G. G. Adelchanov," and from radiovan's child webpage entitled, "Couldn't compete with Mantashev and Aramyants, but was on a par with them: Grigory Adelkhanov's industrial miracle" (parts 1, 2, 3). The two photographs below were colorized wih Lunapic.

G. G. Adelkhanov built a leather-making factory in 1875 equipped with the latest technology: three steam engines with three 55-hp steam boilers running on liquid fuel, forty-two concrete pools, eighteen fermentation vats, thirty-four ash holders and one hundred and four tanning vats, a filtered water supply and a dehydrator for drying wool. Space was deliberately made plentiful to encourage cleanliness and tidiness. The plant housed a rail track used for moving inventory about. Adelkhanov's factory employed about three hundred workers, Armenians, Tatars and Georgians indiscriminately.

The leather plant worked perfectly, and Adelkhanov decided to conflate it with the business of making shoes in 1885. The good quality of the leather produced by the parent factory lowered the production cost of making shoes and earned the company a substantial government contract for provisioning the Caucasian Army with boots.

Next he opened a retail shoe store in 1887.

Adelkhanov shoes were sold mainly in Tiflis, Baku and Vladikavkaz, where the warehouses were.

The brand's goods, which included saddles and suitcases, won awards at major Russian exhibitions time and again.

Adelkhanov created a joint-stock company in 1896 with a starting capital of one and a half million rubles. Around two thousand workers participated.

Aside from managing his businesses, Adelkhanov chaired the trustees' board of the Tiflis Commercial School. He offered graduates from this school a chance to work for his company.

Simultaneously he headed a prison committee overseeing the strict adherence to jailhouse rules for the inmates.

He was also a member of the Tiflis Armenian Charitable and Educational Society.

Grigory Grigorievich Adelkhanov passed away in 1917 at his two-story mansion which was surrounded by a huge orchard on the banks of the Kura River.

When the Bolsheviks invaded Georgia (1921) they gave Adelkhanov's only son and inheritor the post of chief engineer at the plant. Then [date unspecified] they sent him to Germany for the purchase of new equipment. Upon returning from the trip, Adelkhanov Jr. was arrested, accused of sabotage, convicted and sent to the Karganda Correctional Labor Camp (1931-1959) where he perished in murky circumstances.

Adelkhanov Jr. was rehabilitated posthumously in 1957.

The widow of Adelkhanov Sr. was evicted from her mansion and removed to a cramped dark room in a house located behind the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute of Tiflis.

5. THE HAUNTS OF STALIN: BAKU, BATUM, TIFLIS.

Baku: According to a dispatch from St. Petersburg the blaze of Baku's oil wells has occasioned five hundred dead.1

February 1, 1901, started like a normal working day at the oil fields near Baku.

But this day was abnormal for an oil field custodian whose duty it was to prevent oil tank fires by verifying the absence of trespassers, especially mischievous children, on the premises. His job entailed going around and inspecting every oil tank.

The tedious task may have diminished the guard's alertness or dulled his brain. Why so much fuss?—he may have mused, weary—surely no one in his right mind would come to damage or set the oil tanks on fire. Then he acted like a foolish child.

It's unclear why he decided to repeat the "feat" but the patch of fuel oil suspended in a puddle of water would not ignite with the strike of a match! So he decided to try it on a metal tank filled with ninety-six thousand tons of fuel oil!

Batum (Madrid, 27): An enormous explosion has completely destroyed the city. The explosion caused numerous victims. Further details about the catastrophe are unavailable at this time.

Batum (Spain's General Directory of Health): According to official news received in this Centre the port of Batum (Russia) has been declared infected with bubonic plague. Let this be known to all port health authorities and to all consignees whose vessels call on Spanish ports (Madrid. November 12, 1901).

Batum (Madrid 24, 11:00 PM): Telegraph cables from Batum in the Caucasus speak of sanguine riots. A numerous group of socialists tried to assault the prisons and free some comrades locked inside. The troops repelled the assailants, causing thirty dead and many wounded.1

St. Petersburg: The news that three princes received life sentences with hard labour roused the city. Prosecutors showed that the three had committed more than a hundred robberies and murders in the District of Batum.

Batum (Madrid 3, 8:45 PM): Reports from St. Petersburg state that in Batum, a very important port of the Black Sea, enraged strikers accosted by Russian police stormed the Cossacks. The furious strikers marched to different spots in the city and set fire to the majority of public buildings. There was a real tumult in the streets. The number of dead exceeds three hundred.

Vigo: The civil governor informed the Director of Health for the port of Vigo that the restrictions imposed on arrivals from Batum (Russia) and from Alexandria have been lifted.

Amazing data: The newspapers publish a very curious table of volcanic and seismic perturbations registered on the earth since last May 8. [Among them:] June—Baku—The volcano "Gusy-Grau" [today Bolshoy Bozdag] erupts in flames, detonations, and ejects mud for space of five minutes. A "multitude" of boats was destroyed and shepherds killed.

Batum (London): Dispatches from St. Petersburg inform of new disturbances in Batum on the 22nd. The origin of the riot was the send-off given to the lawyers who had come to the city to defend those arrested in a previous riot. The crowd marched through Maria Prospect on their way to the railway station, waving red flags and holding gonfalons inscribed with slogans hostile to the Government.1

Baku: Similar disturbances took place in Baku. Demonstrators handed out inflammatory agitprop and became so menacing that several Cossacks "sotnias" had to come to assist the police. The rioters dispersed when the troops showed up, but presently regrouped and hurled stones at the soldiers and police. The governor was lightly injured. Calm was restored at night. Nineteen rioters were detained.

Tiflis: Three unidentified individuals brandishing daggers assaulted Prince Galitzin the Governor of the Caucasus as he and his wife returned home from a leisure outing. One assailant wounded the princess lightly on her head and hand. The criminals fled headlong but were shot dead by a detachment of Cossacks in hot pursuit.

Baku: The naphtha from the province of Baku is known all over the world and yields 1.5 million metric tons of petroleum.

Tiflis (Madrid, 21): Four armed individuals assaulted a [parked] train of the Transcaucasian Railway, barged into the mail coach, tied up the employees, wounding one, and got away with securities, titles and certificates worth a hundred million rubles.1

Cannons & hailstones. The tsar's rich vineyards near Tiflis cover an area of 155 hectares [383 acres] and since 1901 have cannons stationed for shooting at hail-bearing clouds. In 1901 the fifteen batteries of cannon were active eighteen days and put an end to the serious damage inflicted by hailstorms. Indeed no previous year had passed without the vineyards getting ruined by the hail, but in 1901, thanks to effective cannon fire, hail did not damage the imperial vineyards.

The horrors of war. Le Moniteur Industriel publishes very interesting data on the repercussion of the Russo-Japanese War on commerce in nearly all the provinces of the Russian Empire... The economic consequences of the current conflict are felt as far away as Central Asia and the Caucasus. Baku sells less oil and Tiflis has suspended its exports of wine and fruit.1

Batum (Madrid, 31): Prince "Adell" (?) the head of police was dragged through the streets of Batum and his corpse torn to pieces.1

Tiflis (Madrid, 7): Tiflis has witnessed vicious riots once more. Many striking workers perished in clashes with the troops.1

Tiflis (Madrid, 10): The students of Tiflis went on strike. Railway employees and the butchers second them.

Batum: According to reports from St. Petersburg the strikers tried to kill the stationmaster. The strike continues and the authorities force owners to open their shops. The city garrison was reinforced. The transportation of oil has been suspended.

Tiflis: Such is the anarchy that no newspapers circulate and pharmacies have closed as employees join the strike movement.

Batum (Madrid 14, 10:00 AM): Telegraphs from Paris say that strikers and troops clashed in Batum, leaving several dead and wounded.

Batum: Faced with unrest in the Caucasus the government refrained from deploying three hundred thousand soldiers to Manchuria for the reinforcement of Kuropatkin's army.

More workers go back to work in Batum.

Tiflis: The agitation is enormous. The mayor was wounded by a shot from an unidentified gunman. A mob killed a justice officer named "Goudiv" (?).

Baku (Madrid 22, 8:00 PM): The unrest in Baku worsens. Clashes between police, troops and the people left many dead and wounded. Mobs assault and ransack shops. Many houses were torched. The troops are powerless to contain the masses and panic grips the affluent classes.1

Baku: The civil war reaches Baku.1

Tiflis: Clashes continue between troops and strikers. Official buildings, schools and big shops remain closed. The streets are full of corpses. Criminals take advantage of the exceptional circumstances and despoil vacant homes. The panic is immense.2

2 On February 15 (28) Stalin wrote another pamphlet entitled, "To Citizens. Long Live the Red Flag!" in connection with a peace march held in Tiflis. The leaflet relates that on February 13 (26) "many thousands" of Armenians, Georgians, Tartars and Russians assembled in the enclosure of Vanque Cathedral to take a vow of mutual aid "in the struggle against the devil who is sowing strife among us." The Bolsheviks infiltrated the religious assembly and distributed three thousand leaflets. On February 14 (27) the entire cathedral enclosure and the adjacent streets were packed with people, says Stalin. The Bolsheviks hijacked the event and converted a religious gathering into a revolutionary rally. Twelve thousand flyers were distributed that day. To abolish pogroms and to cease the national strife, the flyer told the demonstrators, you must strive for the triumph of socialism, ceding leadership to the proletariat, for "the proletariat, and only the proletariat, will win freedom and peace for you." Five slogans close this publication, Down With the Tsarist Autocracy!, Long Live the Democratic Republic!, Down With Capitalism!, Long Live Socialism! and Long Live the Red Flag!

Batum (Madrid 27, 3:00 AM): Troops occupied the working-class neighbourhood of Batum; an officer and several soldiers were hurt. A cache of weapons was uncovered.

Batum, Tiflis: The insurrection gains ground in Batum and in Tiflis with bloody clashes taking place. Two thousand people were killed, thousands more wounded, since the unrest began.

Batum: A stench hangs over Batum because hundreds of decomposing corpses lie out in the open.

Mutineers killed the police prefect and a Cossack commander.

Kutais (Madrid 1, midnight): Reports from Tiflis say that the agitation in the Kutais districts is horrible.1 The Government has sent General Alikhanov there with numerous forces and special corps.

Batum: Recent clashes have left two thousand dead and countless wounded.

Batum (Madrid 13, 11:30 PM): Telegrams from Batum report that the Mingrelians began an uprising.1 The government is urgently sending the forces required to suppress the insurrection.

Tiflis: The insurrection worsens. Peasants burn and plunder the landed estates.

Tiflis (Madrid 2 [?], 10 PM): Dispatches from Tiflis say that four perfectly armed men held up the railway station and got away with six thousand rubles. The police is after them.

Tiflis: In many Guria towns the peasants commit all type of excesses against clergy and houses of the nobility, pillaging and burning the houses and wasting the woodlands. The police charged the rioters, killing and injuring many.

Baku: Three cases of cholera were tallied yesterday, one fatal. The local Commission does not have enough funds to tackle the epidemic.

Tiflis (Madrid 9, midnight): Six thousand rifles were stolen from the state armoury of Tiflis.

Baku (Madrid 25, 4:00 AM): Reports from Baku state that the Governor was assassinated by a pedestrian who lobbed a bomb at his carriage. The driver was gravely injured as were other persons nearby.

Tiflis (Madrid 6, 10:00 PM): Reports from the Russian capital inform that strikers and troops exchange fire on the streets of Tiflis.

Tiflis (Madrid 10 [?], 10:00 AM): In Tiflis a student threw a bomb at a group of soldiers. Fifteen perished, twenty were wounded.1

In the article Stalin exposes the three-day street fighting of Lodz, the huge strike of Ivanovo-Voznesensk, the Odessa uprising, the Potemkin mutiny, the rebellion inside Libau's naval depot and the "week" in Tiflis as harbingers of the irrestible revolutionary storm approaching. These new characteristics of life demand of the Party an active role in the uprising, he maintains. The Party's new task is to afford technical guidance and conduct the all-Russian revolution. The proletariat will steer the revolution to install a democratic republic convenient for the next step to socialism.

Thus the Party's immediate practical task—urges Stalin—is to arm the people forthwith, to procure weapons,a start undergound workshops for making explosives b and seize armouries, state or private.c It is permissible and absolutely essential to cooperate with all other Social Democratic sections for the sole purpose of procuring arms.

The Party's second practical task is to train special fighting squads with the help of Party members with military experience. The fighting squads will come out as the chief leading units around which the insurgent people will rally during an uprising.d They will quickly take over armouries, government offices, public buildings, the Post Office, the telephone exchange, and so forth, and thus propel the revolution forward. The armed fighting squads, ready to go out in the streets and take their place at the head of the masses of the people at any moment, can easily achieve the objective of the Third Party Congress to combat the Black Hundreds (see Collected Works of V. I. Lenin & Galiciana, Chapter 7, Item 3) and all reactionary elements ascribed to the government.

Only a thorough preparation for an insurrection—concludes Stalin—can guarantee that Social-Democracy will head the forthcoming battles between the people and the autocracy.

a See the news for October 22, 1906.

b See the news for January 12, April 30 and May 17, 1906.

c See the news for May 10, 1905.

d See the news for July 7, September 14 and 21 of the year 1905 and the news for January 23, 1906.

Tiflis (Madrid 2, 4:00 AM): Dispatches from St. Petersburg inform that a serious uprising took place in the region of Tiflis. There were numerous massacres between Tartars and Armenians.

Baku (Madrid 10, 10:00 PM): Foreigners, among them many British subjects, are under persecution in Baku. The Governor is helpless to rescue them. Many have taken refuge on board ships.

Baku, 9: The Tartars have slain four hundred Armenians who had sought refuge in a courtyard. Thousands more have for five days been under siege by Tartars in Zabrat.

Baku (Madrid 13, 4:00 AM): Clashes persist in Baku. Eight neighbourhoods were razed. Complete anarchy reigns.

Tiflis, 12: The troops of Baku are exhausted after their heavy toil. Law and order are still lacking. The governor's orders can not be followed since there is not enough personnel. All arsonists and assailants will be shot on sight. The workers responsible for all the rioting are now poverty-stricken.

Baku (Madrid 14, 10:00 AM): Reports from Baku say that street shooting continues. Muslim policemen side with the Tartars.

The crimes of the Tartars: The total wreck of the big industries of Baku is confirmed.

The Tartars slew nearly all the Armenian residents of Baku and plundered neighbouring hamlets.

One dispatch states that access to Baku is impossible and that its streets are full of corpses. The exact number of victims is unknown, but it is certain that the number is considerable. There is no information about what is happening in towns close to Baku that have fallen into the hands of the Tartars. Withal not enough troops have been sent to impose law and order.

Hundreds of fleeing Armenians were murdered by Tartars on a road leading out of Baku.

Four hundred Armenians who took refuge in a house were stabbed to death; soldiers assisted the Tartars in their sinister doings. Not even Turkey has witnessed anything like the shameful and bloody incidents of Baku.

The Government of St. Petersburg excuses itself saying it does not possess sufficient information.

Tiflis: Police dissolved the democratic committee lodged at the Municipal Palace in a skirmish that left many dead and wounded.

Tiflis, 13: Companies involved in the naphtha industry have met and convened that they will not resume work until they receive full security guarantees and the Tartars are disarmed and removed from the city.

St. Petersburg, 13: The British vice consul in Baku telegraphed that all British subjects there are safe and sound.

Baku (Madrid 18, 7:00 PM): The Tartars continue wrecking the oil wells of Baku, very few remain intact. All those who attempt to stop the systematic destruction are put to the blade.

Batum (Odessa, 17): Reports arriving from Batum are very alarming. It is feared that many slaughters will be committed there as they were in Baku.

Tiflis, 17: The entire City Hall resigned over the bloody military suppression of the last demonstration. Shops and industrial centers are closed in a show of mourning. The revolutionary Committees of Tiflis have published much agitprop harbinging a general uprising.

Baku: More troop reinforcements are being sent to Baku where the city's aldermen have fled.

Batum: It is feared that the revolutionaries will reproduce in Batum the horrors and massacres of Baku; i.e., the movement has spread from the East to the West of the Caucasus, from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea.

The authorities have chartered four steamboats to carry troops to Batum.

Letters seized from Turkish agitators in Batum incite the Tartars to a general uprising, promising the undercover support of the Sultan for now, and later the assistance of the Turkish Army and Navy for rescuing Muslim territory from the Christian power. Many of Batum's Muslims involved in the plot unveiled by these letters were detained.

Baku: Arson attacks in Baku have destroyed thirty private estates and the installations of twenty-one Companies.

Tiflis (Madrid 20, 11:00 PM): News from Tiflis say that banditry rules the country. The revolutionaries plundered Guria after waging real battles with gendarmes which left many dead. Assassinations and arson continue.

St. Petersburg, 19: Tartars assaulted five trains full of Armenian fugitives in the district of Shusha and slew the men. Armed Ossetians in Guria pillage the stores and houses of shop owners. The clashes resulted in many dead and wounded.

Baku: Murders, robberies and arson persist in Baku.

Baku (Madrid 23, 4:00 PM): Reports from Baku say that the foreign consuls stationed there asked their respective countries to send troops to protect their nationals.

Baku, 21: Although tempers remain on edge, a move to return to work has begun, and so have shipments of naphtha and other wares.

Batum, 21: The city remains quiet. Ships arrive and leave normally.

Baku, 24: The Consul of Persia says that 1,500 Persian workers were expelled from Baku. He adds that a similar number will be expelled shortly.

Baku (London, 24) Several newspapers publish a dispatch from St. Petersburg stating that there is no running water in Baku. Aldermen, doctors and engineers have fled.

Baku (Madrid 9, 11:45 AM): The disorders continue in Baku. Robberies and murders are a daily occurrence. New troop reinforcements have not succeeded in restoring calm.

Tiflis (Paris, 11): Dispatches out of Tiflis say that a hand grenade thrown near the Opera House caused at least twenty victims.

Baku (Madrid 27, 11:00 AM): According to press reports from Moscow a mechanic who tried to commandeer a locomotive in Baku was heaved by striking railwaymen into the boiler where he perished horribly scorched.1

Batum: A general strike was declared. The governor ordered troops to fire live ammunition.

The railway companies are compelled by law to feed and assist some thirty thousand passengers left stranded at various stations because of the strike.

Batum (Madrid 9, 4:00 AM): A bomb exploded at the Cossack garrison of Batum, killing a hundred Cossacks and wounding a hundred and fifty.

Batum (Madrid, 17): The insurgents have raised barricades on the streets of Batum.

Tiflis: The massacre of Christians continues. They suffer horrendous tortures on the back of all kinds of abuses.

Tiflis, Batum (Madrid 22, 3:00 AM): News from the Caucasus say that the Armenians are the lords of Tiflis and that Batum is in flames.

Tiflis (Madrid, 11, 12:00 noon): Reports from Russia inform that a state of siege has been declared in the region of Tiflis after the discovery of a large cache of bombs [hand grenades] set ready to be used. Many arrests were made.

Baku: The Tartars attacked Tiflis but were repulsed.

Tiflis, 15: Railway traffic between Tiflis and Baku was reestablished yesterday.

Batum: Telegrams from St. Petersburg confirm the taking of Batum by the revolutionaries.

Guria (Madrid 27, 11:00 AM): It is said from Russia that a detachment of Guria troops was ambushed and taken prisoner by the revolutionaries.

Tiflis (Madrid 31, noon): The chief of staff was murdered in Tiflis with a hand grenade. The assassin was arrested.

Tiflis (Madrid 30, 10:00 AM): Police discovered an important workshop for making explosives in Tiflis. Twenty-four revolutionaries were arrested on suspicion of being involved.

Tiflis (Madrid 15, 3:00 PM): Dispatches from St. Petersburg state that Tiflis police discovered a cache of around two hundred bombs.

Batum (Madrid 22, 10:00 AM): The Yankee Vice-Consul of Batum was murdered. The assassin fled.

Tiflis (Madrid 6, 2:30 PM): A general strike began in Tiflis. The situation is deemed truly grave.

Tiflis (Madrid 19, 0:45 AM): Telegrams from St. Petersburg inform about the assassination of General Maximov in Tiflis. Many arrests were made.

Tiflis (Madrid 20, 4:00 AM): A hand grenade hurled out of a window of the school for Georgian nobles in Tiflis exploded near the palace of the governor of the Caucasus. Police killed one author of the attack and wounded another.

Batum (Madrid 4, 4:00 AM): The representative of Sweden in Batum was assassinated.

Poland (Madrid 21, 10:00 PM): Reports from St. Petersburg say that Custom officials in the Government of Lomza [Poland] have seized nine packages sent from Berlin to Tiflis containing fourteen thousand cartridges.

Tiflis (Madrid 10 [?], 4:00 PM): An attempted robbery of a train transporting money in Tiflis was repelled by soldiers after a hard firefight. Both sides suffered casualties, dead and wounded.

Tiflis (Madrid 13, 10:00 PM): Terrorists threw a bomb on Golavinaki Prospect in the Caucasian capital which left General "Sevreinov", the wife of General "Kiaganov" and the engineer "Artasov" badly injured. Artasov died of his wounds last night.1

Tiflis (Madrid, 4): Terrifying earthquakes shake the Caucasus. The city of Tiflis was completely levelled; its rubble-strewn streets are full of corpses.

Tiflis (Madrid 27, 3:00 PM): Ten bombs were thrown into a crowded Yerevan Square. The bombs exploded causing an "infinite" number of victims and great property damage.1

Baku: Telegraphs from Constantinople report the incidence of cholera in Baku. The epidemic is causing many victims.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |